On This Day: 1744 - War of the Austrian Succession: The Battle of Toulon causes several Royal Navy captains to be c

By the early weeks of 1744, the Mediterranean had become a pressure cooker of geopolitical ambition and personal loathing. The War of the Austrian Succession, which had ignited in 1740 over the right of Maria Theresa...

By the early weeks of 1744, the Mediterranean had become a pressure cooker of geopolitical ambition and personal loathing. The War of the Austrian Succession, which had ignited in 1740 over the right of Maria Theresa to inherit the Habsburg throne, had long since ceased to be a mere dynastic dispute in Central Europe. It had evolved into a sprawling maritime struggle, pitting the Bourbon powers of France and Spain against the British Empire. Off the coast of Toulon, a British fleet had spent months in a grueling blockade, its crews withered by scurvy and its timbers fouled by weeds. Yet the greatest threat to British naval supremacy did not lie in the cannons of the enemy, but in the toxic relationship between the two men leading the blockade: Admiral Thomas Mathews and Vice-Admiral Richard Lestock. These two officers despised one another so thoroughly that they had ceased to communicate through any means other than formal, icy correspondence, even as a combined Franco-Spanish fleet prepared to break out of port.

Immediate Causes

The strategic impetus for the confrontation on February 22, 1744, was the necessity of maintaining the “Pragmatic Sanction,” a legal mechanism intended to ensure the integrity of the Austrian Empire. Spain sought to reclaim lost Italian territories, while France, though not yet officially at war with Britain, provided naval support to their Spanish cousins under the Bourbon Family Compact. For the British, the Mediterranean was the vital artery of their continental strategy. If the Spanish fleet at Toulon could unite with the French fleet at Brest, they would possess the numerical superiority required to launch an invasion of the British Isles or decimate British trade.

Internal professional friction within the Royal Navy served as the immediate combustible material. Admiral Mathews, a man of legendary irascibility, had been brought out of retirement to command the Mediterranean fleet, largely because of his reputation for aggressive action. Conversely, Vice-Admiral Lestock was a master of naval technicalities and a man who prided himself on rigid adherence to the “Fighting Instructions”-the tactical manual of the era. The two men had a history of mutual professional sabotage dating back years. By the time the combined enemy fleet began to warp out of Toulon harbor on February 19, 1744, the British command structure was effectively decapitated by ego.

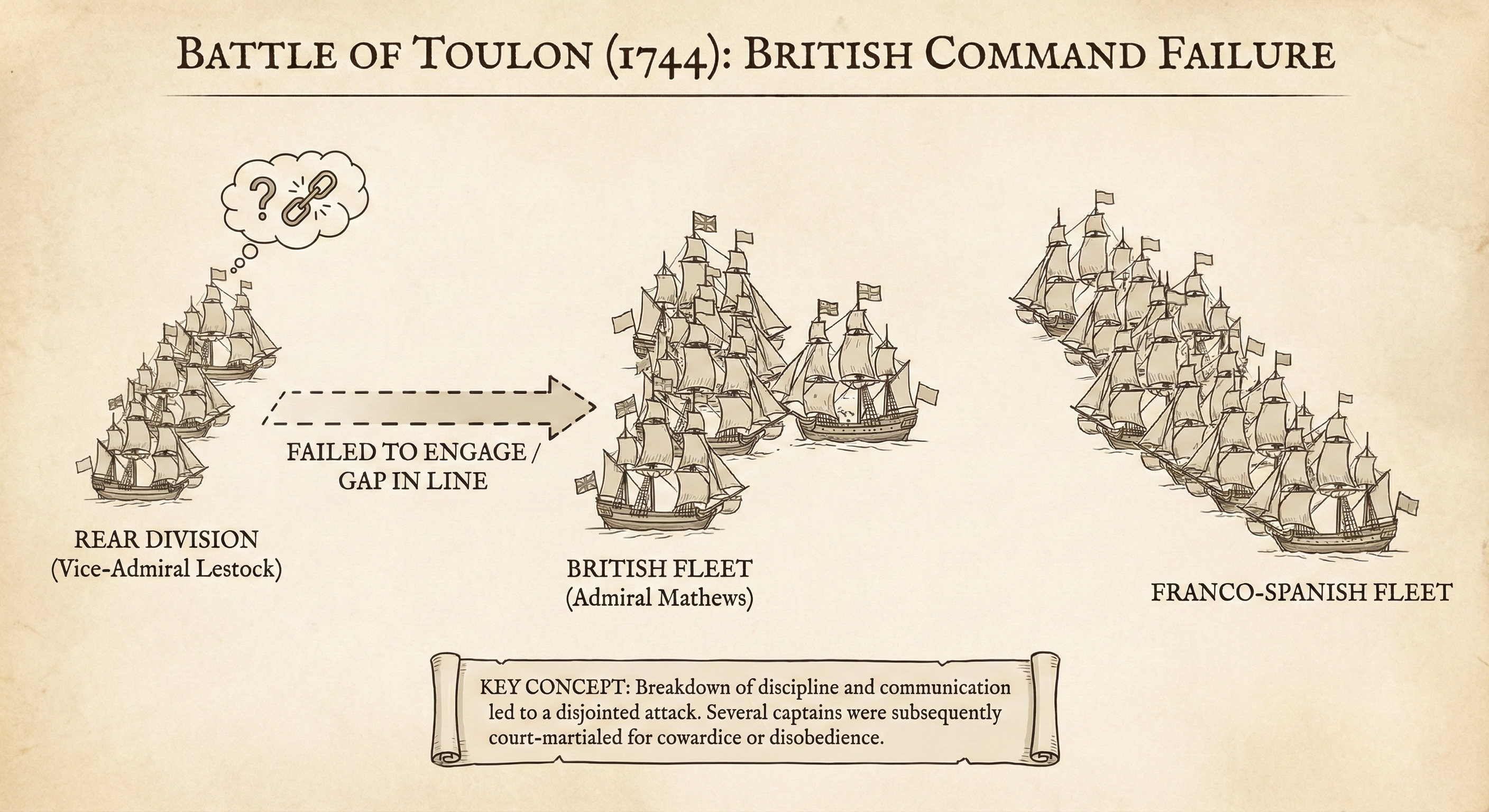

The tactical cause of the disaster was the sheer rigidity of the Fighting Instructions. These rules mandated that a fleet must maintain a continuous “Line of Battle” to maximize broadside fire and minimize the risk of being “doubled” (attacked from both sides). On the morning of February 22, 1744, as the British chased the retreating Franco-Spanish line, the wind was light and the sea state was erratic. Mathews, fearing the enemy would escape into the Atlantic, felt compelled to attack immediately. However, his fleet was spread out over several miles, and Lestock’s division trailed far to the rear, separated by a gap that made a coordinated strike impossible without a significant delay.

How the Event Played Out

The battle commenced on the afternoon of February 22, 1744, approximately thirty miles off the coast of Toulon. Admiral Mathews, flying his flag on the 90-gun Namur, observed the Spanish rear-guard lagging behind the French van. Sensing a fleeting opportunity to crush the Spanish contingent before the French could come to their aid, Mathews signaled for his fleet to engage. However, he faced a technical dilemma: to engage the enemy, he had to break his own line, but the signal for “Line of Battle” remained flying at the masthead of his flagship. To Lestock, watching from the Neptune miles astern, this was a moment of malicious opportunity.

As Mathews and his center division plunged into the Spanish line, Lestock remained largely inactive. He argued that as long as the “Line of Battle” signal was hoisted, he was legally prohibited from breaking formation to join the fray, despite the obvious necessity of the situation. The result was a chaotic and fragmented engagement. Mathews and Captain James Berkeley of the Revenge found themselves in a brutal close-quarters duel with the Spanish flagship Real Felipe. For hours, the two sides exchanged devastating broadsides, yet the expected support from the British rear never arrived.

The French commander, Claude-Éloi de Court de La Bruyère, eventually tacked his ships back toward the melee to rescue the beleaguered Spanish. Fearing his fragmented fleet would be overwhelmed, Mathews was forced to signal a retreat as darkness fell. While the British had technically held the field and prevented the enemy from achieving their primary objective, the escape of the Franco-Spanish fleet was viewed as a humiliating failure. The British had 30 ships of the line against 27 for the Bourbon allies, yet they had failed to capture or sink a single significant vessel, while the Namur and Marlborough were left as drifting wrecks.

Early Consequences

The immediate aftermath of the Battle of Toulon was a firestorm of public outrage in London. The failure of a superior British force to achieve a decisive victory against the “Papist” powers was seen as a sign of national rot and military incompetence. By the end of 1744, the Admiralty was besieged by demands for accountability, leading to a series of inquiries that would eventually culminate in the largest mass court-martial in the history of the Royal Navy.

The Mediterranean fleet had become a house divided against itself.

Between 1745 and 1746, eleven captains and two admirals were brought to trial to answer for their conduct during the engagement. The proceedings were highly politicized and highlighted a profound rift in naval philosophy. Captains who had followed Mathews into the thick of the fight were sometimes censured for technical breaches of the Fighting Instructions, while those who had hung back were accused of cowardice. The most shocking outcome, however, was the fate of the two commanders. Admiral Mathews, who had actually fought the enemy, was found guilty of “neglect of duty” and dismissed from the service in 1747, primarily because he had broken the line. Conversely, Vice-Admiral Lestock, who had arguably sabotaged the battle through his calculated inaction, was acquitted on the grounds that he had strictly followed the standing orders regarding the Line of Battle.

Competing Historical Interpretations

Historians have long debated whether the failure at Toulon was a failure of personality or a failure of doctrine. The “Technicalist” school of thought argues that the British naval system of 1744 was fundamentally flawed. These historians posit that the Fighting Instructions had become a “tactical straitjacket” that prioritized order over victory. In this view, Lestock was not a villain but a victim of a system that punished initiative and rewarded rigid conformity to the rules of engagement. They suggest that the battle proved that the “Line of Battle” was an obsolete concept when faced with light winds and a retreating enemy.

The “Biographical” school of interpretation shifts the blame onto the toxic leadership of Mathews and Lestock. These scholars argue that no amount of tactical flexibility could have overcome the spiteful lack of communication between the two admirals. They point to the fact that other British commanders later in the 18th century, such as Horatio Nelson, frequently broke the line with great success because they possessed the professional trust of their subordinates. In this interpretation, Toulon was a “moral defeat” where the social and professional fabric of the officer corps disintegrated under the weight of petty grievances.

A third, more modern interpretation focuses on the “Professionalization Crisis” of the 18th-century navy. This perspective suggests that the Royal Navy was in a painful transitional phase between an era of aristocratic amateurism and a modern, professional bureaucracy. The Battle of Toulon exposed the lack of a standardized signal book and a clear legal framework for command, forcing the British government to intervene in naval affairs in a way it never had before. This interpretation sees the subsequent court-martials not as a pursuit of justice, but as an attempt by the British Parliament to exert civilian control over an increasingly powerful military institution.

Long-Term Impact

The legacy of February 22, 1744, was etched into the very legal and cultural foundations of the Royal Navy for the next century. The most concrete result was the drastic amendment of the Articles of War in 1749. Parliament, appalled that Lestock had been acquitted on a technicality while the fighting admiral was dismissed, sought to ensure that no officer could ever again use the “letter of the law” to excuse a failure to engage the enemy. The new Article XII was made ruthlessly specific, stating that any officer who failed to do his utmost in battle out of “cowardice, negligence, or disaffection” would be sentenced to death, with no room for the court to mitigate the penalty based on circumstances.

The amendment of the Articles of War in 1749 removed the discretion of court-martial boards to mitigate the death penalty for cowardice or negligence, a change that would eventually lead to the execution of Admiral John Byng on March 14, 1757. Byng’s death-shot on his own quarterdeck after failing to relieve Menorca-was a direct “aftershock” of the Battle of Toulon, as the judges felt their hands were tied by the laws written in the wake of Mathews’ and Lestock’s failures. This harsh legal environment forced a culture of extreme aggression within the Royal Navy, where commanders knew that anything less than total commitment to the attack could result in a firing squad.

Beyond the legal changes, the Battle of Toulon catalyzed the development of more sophisticated signaling systems. It became clear that the flag signals used on February 22, 1744, were dangerously ambiguous, especially when an admiral wished to transition from a cruising formation to an attack formation. This led to the innovations of Richard Howe and Kempenfelt later in the century, ultimately providing the tactical clarity that allowed for the decisive victories of the Napoleonic Wars. The humiliation off the coast of France in 1744 was the bitter medicine that transformed the Royal Navy from a collection of bickering captains into the disciplined, aggressive, and technically superior force that would dominate the world’s oceans for the next 150 years.

Sources

- War of the Austrian Succession: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_the_Austrian_Succession

- Battle of Toulon (1744): https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Toulon_(1744)

- Royal Navy: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Navy

- Court-martial: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Court-martial

- Articles of War: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_War

- Rodger, N.A.M. The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815. (Reference lookup recommended).

- Willis, Sam. Fighting at Sea in the Eighteenth Century: The Art of Sailing Warfare. (Reference lookup recommended).