On This Day: 1943 - The Saturday Evening Post publishes the first of Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms in support of

The crisp scent of ink on paper met millions of Americans as they opened the February 20, 1943, issue of *The Saturday Evening Post* to find a blue-collar laborer standing in a crowded room, his mouth open, his eyes f...

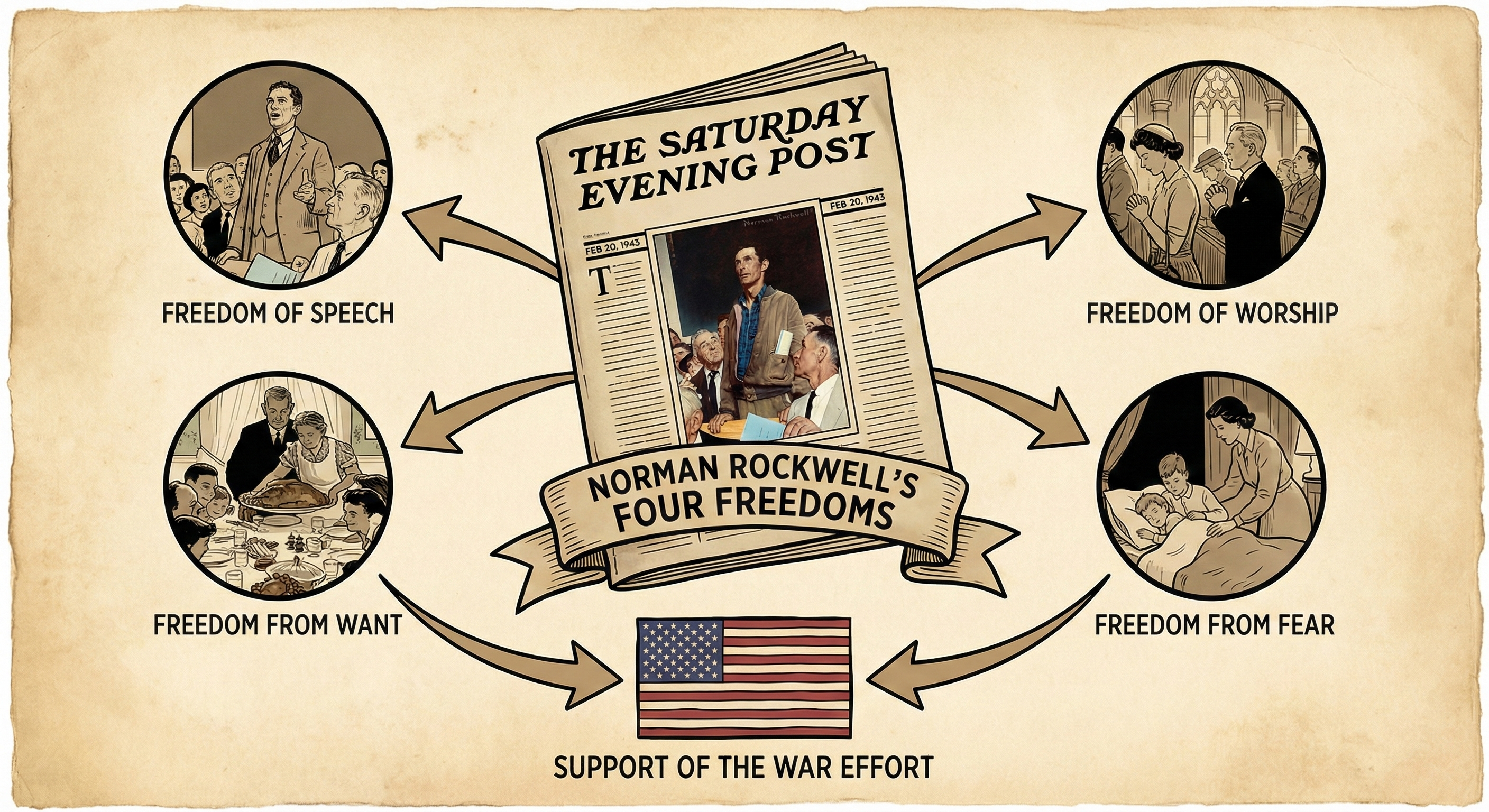

The crisp scent of ink on paper met millions of Americans as they opened the February 20, 1943, issue of The Saturday Evening Post to find a blue-collar laborer standing in a crowded room, his mouth open, his eyes fixed on an unseen ideal. This was the moment abstract political philosophy became a tangible, visual reality. For two years, the United States government had struggled to articulate exactly what the nation was fighting for in the Second World War, but within the brushstrokes of Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech, the answer finally became clear to the American public. The publication of this first painting marked a decisive shift in wartime domestic propaganda, moving away from bureaucratic messaging toward an emotional, humanized iconography that would eventually raise over $130 million for the war effort.

Quick Historical Background

The conceptual framework for Rockwell’s masterpiece did not originate in an artist’s studio, but rather in the halls of the United States Capitol. On January 6, 1941, nearly a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt delivered his State of the Union address, a speech later immortalized as the “Four Freedoms” speech. Roosevelt outlined a vision for a post-war world founded upon four essential human freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

Despite the gravity of the speech, the American public’s initial reaction was tepid. The concepts were viewed as overly intellectual or too European in scope. By early 1942, with the United States fully embroiled in the conflict following the December 7, 1941, attack on Hawaii, the Office of War Information (OWI) searched for a way to “sell” these freedoms to a skeptical or distracted populace. Norman Rockwell, already a household name for his nostalgic covers for The Saturday Evening Post, saw the opportunity to translate these grand ideals into the language of everyday American life. He initially approached the OWI in Washington, D.C., in mid-1942, but he was famously rebuffed by officials who told him that “fine arts men” would be used for the war’s posters, not commercial illustrators.

Key Moments in Sequence

The journey from Roosevelt’s podium to the printed page was a grueling process of creative refinement and bureaucratic rejection. After being turned away in Washington, Rockwell returned to his home in Arlington, Vermont, determined to prove the OWI wrong. During a local town meeting in 1942, he observed a neighbor, Jim Edgerton, stand up to voice an unpopular opinion. Though everyone in the room disagreed with Edgerton, they listened in respectful silence. This local moment provided the spark Rockwell needed to visualize the first freedom.

The timeline of production and publication followed a precise trajectory:

- May 1942: Rockwell visits the Office of War Information with sketches but is rejected.

- June 1942: On his return trip, Rockwell stops at the Philadelphia offices of The Saturday Evening Post and meets with editor Ben Hibbs.

- Summer 1942: Hibbs immediately commissions the series, giving Rockwell a full year of creative freedom and a reprieve from other assignments.

- November 1942: Rockwell nearly loses his progress when a fire in his studio destroys several sketches, though the Four Freedoms canvases are fortunately elsewhere.

- February 20, 1943: The Saturday Evening Post publishes Freedom of Speech as the first installment in a four-week consecutive series.

Throughout the autumn of 1942, Rockwell labored over the details. He used his neighbors as models, dressing them in worn clothing to emphasize the “everyman” quality of the struggle. For Freedom of Worship, he painstakingly arranged figures of different faiths into a tight, prayerful composition. By the time the first issue hit newsstands in February 1943, the artist had lost ten pounds from the sheer stress of the project.

Inflection Point

The publication on February 20, 1943, acted as a catalyst that transformed the American home front’s psychological relationship with the war. Before this date, the “Four Freedoms” were seen as a Roosevelt policy initiative; after this date, they were seen as a moral imperative. By placing a common laborer in a worn suede jacket at the center of the first painting, Rockwell bridged the gap between the lofty rhetoric of the Atlantic Charter and the lived experience of the American working class.

The image provided a visual anchor for a national identity that felt increasingly fragmented by the rapid mobilization of industry and the military.

The success of the first publication was so immediate that the Office of War Information, which had previously dismissed Rockwell, reversed its stance within days of the February 20, 1943, release. The government realized that Rockwell had achieved what their departments of psychologists and writers could not: he had made the war personal. This inflection point moved the Four Freedoms from the realm of political science into the realm of popular culture, ensuring that the visual language of the paintings would dominate American consciousness for the remainder of the 1940s.

Evidence and Historical Debate

Historians and art critics have long debated the merits and the “truth” of Rockwell’s depictions. On one hand, the evidence of their effectiveness is quantifiable. Following the publication of the series in The Saturday Evening Post, the magazine received 25,000 requests for reprints in just the first few weeks of 1943. When the original paintings went on a national tour beginning in 1943, they were seen by 1.2 million people and were directly responsible for the sale of $132,992,539 in war bonds.

However, a significant historical debate centers on whether Rockwell’s work was a form of “sanitized” propaganda. Critics such as Clement Greenberg, writing in the mid-20th century, often dismissed Rockwell’s style as “kitsch,” arguing that it presented a nostalgic, white-centric view of America that ignored the racial segregation and labor unrest of 1943. Specifically, in Freedom of Worship, Rockwell included a phrase “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience,” yet the faces in the painting were notably homogeneous. Modern historians, examining the works from the perspective of 2024, often point out that while the paintings were revolutionary in their humanism, they also reinforced a specific, idealized version of “Americanness” that excluded the reality of Japanese internment camps or the Jim Crow laws active during that same period.

Aftermath and Follow-Through

The legacy of the February 20, 1943, publication extended far beyond the conclusion of World War II in September 1945. The images were reprinted by the millions and distributed to schools, post offices, and community centers. The Saturday Evening Post and the U.S. Treasury Department collaborated on a massive promotional campaign that saw the paintings travel to 16 different cities. This tour was a logistical feat that required constant security and climate-controlled environments, which was rare for commercial illustrations at the time.

The four paintings-Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear-became the definitive visual shorthand for the mid-century American Dream. Rockwell’s Freedom from Want, depicting a family gathered around a Thanksgiving turkey, became so iconic that it has been parodied and replicated in countless films and advertisements throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Even the United Nations, established in 1945, drew upon the spirit of these four principles when drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The ultimate impact of the February 20, 1943, publication was the validation of the “middle-brow” artist as a vital contributor to national discourse. Rockwell proved that art did not need to be abstract or avant-garde to be intellectually significant. By the time Rockwell died on November 8, 1978, the Four Freedoms remained his most celebrated achievement, a testament to a four-week span in early 1943 when a magazine and an illustrator successfully defined the moral stakes of a global catastrophe.

Sources

- The Saturday Evening Post: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Saturday_Evening_Post

- Norman Rockwell: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_Rockwell

- Four Freedoms (Norman Rockwell): https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_Freedoms_(Norman_Rockwell)

- Franklin Roosevelt: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin_Roosevelt

- State of the Union address: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/State_of_the_Union_address

- Four Freedoms: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_Freedoms

- “Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People,” High Museum of Art (reference lookup recommended).

- “The Four Freedoms: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Era of Hope,” Oxford University Press (reference lookup recommended).