On This Day: 1714 - The battle of Napue between Sweden and Russia is fought in Isokyrö, Ostrobothnia

The biting frost of February 19, 1714, clings to the pines of Isokyrö, a landscape where the breath of men and horses hangs in thick, crystalline plumes. In the historical province of Ostrobothnia, the sun struggles to rise over a horizon heavy with the promise of more snow, casting long, pale shadows across the frozen Kyronjoki river. Here, General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt stands amidst a patchwork force of Swedish regulars and Finnish levies, their boots sinking into the drifts. They are hungry, they are outnumbered, and they are the final barrier between the advancing Russian tide and the heart of the Finnish interior. Across the white expanse, the scouts report a dark mass on the horizon-the approach of Prince Mikhail Golitsyn’s infantry and Cossack cavalry. The silence of the morning is about to be shattered by the roar of cannon fire, marking the commencement of the Battle of Napue.

Historical Context

By the arrival of 1714, the Great Northern War had been raging for fourteen years, transforming the power dynamics of Northern Europe. The Swedish Empire, which had entered the 18th century as the undisputed hegemon of the Baltic, was in a state of terminal overstretch. The catastrophic defeat of King Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava on June 27, 1709, had shattered the myth of Swedish invincibility and left the King an exile in the Ottoman Empire. While the King remained absent, the Tsardom of Russia, under the energetic and ruthless leadership of Peter the Great, seized the opportunity to dismantle the Swedish domains piece by piece.

Russia’s objective was clear: secure a “window to the West” by dominating the Baltic coastline. To achieve this, Finland-then an integral part of the Swedish realm-had to be neutralized or occupied. Throughout 1713, Russian forces had pushed steadily northward and westward, capturing Helsinki and Porvoo. The Swedish defense of the Finnish east had largely collapsed, leaving the task of resistance to General Armfeldt and his meager army of roughly 5,000 men.

The strategic situation in February 1714 was desperate. Armfeldt had retreated into Ostrobothnia, hoping the harsh winter and the difficult terrain would slow the Russian advance. However, Peter the Great had ordered Prince Golitsyn to pursue and destroy the remaining Swedish forces to ensure that no counter-offensive could be launched while the Russian navy dominated the Gulf of Finland. The village of Napue in the parish of Isokyrö became the site where the Swedish army would make its final stands of the Finnish campaign.

What Happened

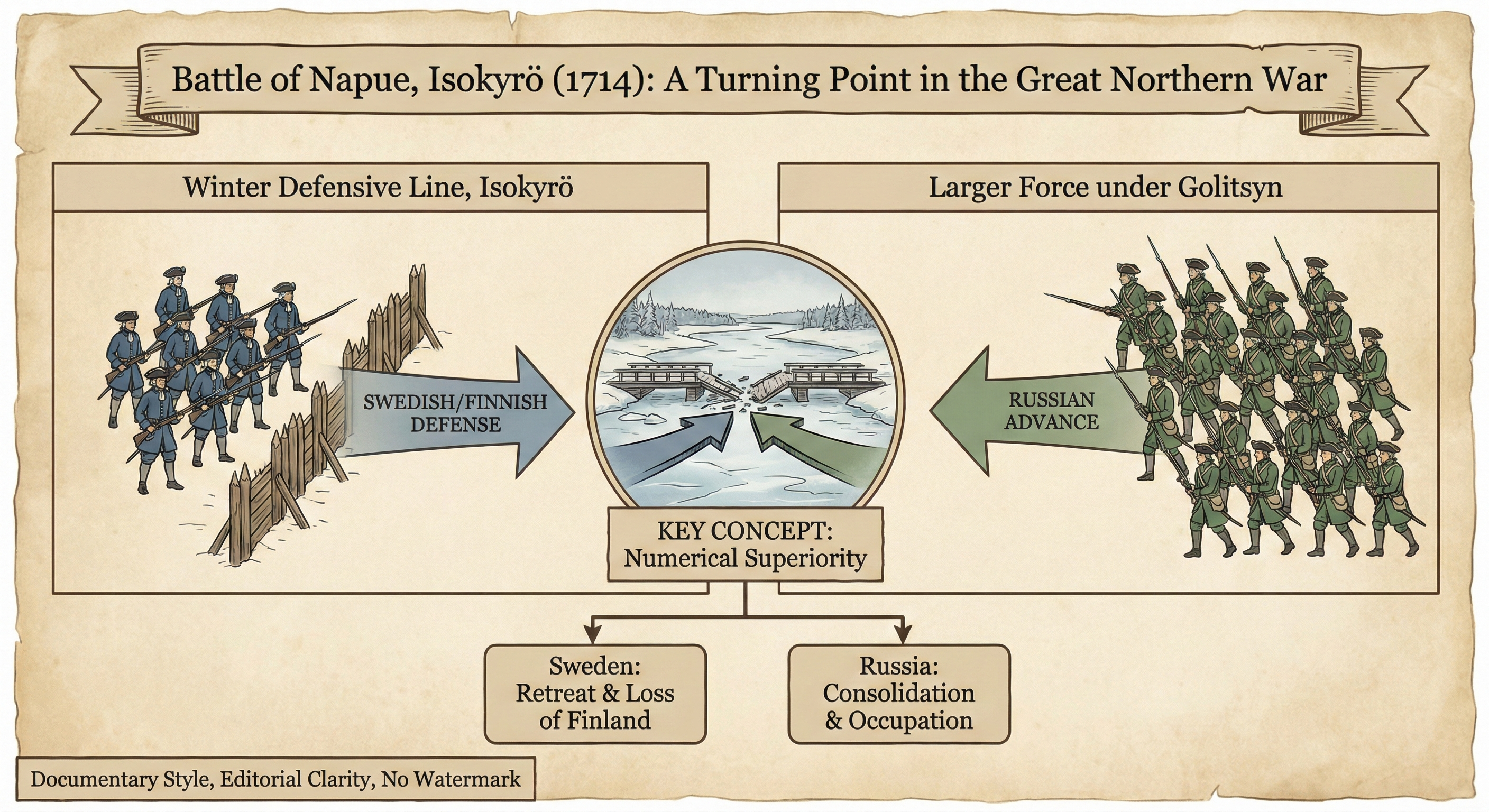

The engagement on February 19, 1714, was a clash of differing military philosophies and a testament to the brutal effectiveness of Russian tactical evolution. Armfeldt had positioned his troops in a strong defensive line near the village of Napue, utilizing the frozen river and the surrounding marshy terrain to protect his flanks. He relied on the traditional Swedish “Gå-På” method-a high-aggression tactic where infantry advanced under heavy fire to deliver a single, devastating volley at close range before charging with bayonets and pikes.

Prince Golitsyn, leading a force of approximately 8,500 to 11,000 men, recognized the strength of the Swedish frontal position. Rather than a direct assault, he executed a sophisticated and grueling maneuver. Under the cover of the morning mist and the deep snow, he sent a significant portion of his infantry and Cossack cavalry through the thick forests and frozen bogs to outflank Armfeldt’s left wing.

When the Russian main body appeared on the field, Armfeldt was forced to adjust his lines. The battle began with a Swedish counter-attack that initially saw some success. The Swedish right wing, composed of hardened regulars, managed to push back the Russian center, nearly breaking their line. For a brief moment in the mid-afternoon of February 19, 1714, it appeared that the Swedish Empire might secure an improbable victory.

However, the superior numbers and the flanking maneuver of the Russians soon turned the tide. The Russian troops who had circled through the woods emerged on the Swedish rear and left flank. The Finnish levies, many of whom were poorly armed peasants, found themselves trapped between the disciplined Russian line and the encroaching pincer. The Swedish cavalry, hampered by the deep snow and exhausted by the long campaign, could not effectively counter the mobile Cossacks.

The “Gå-På” charge sputtered out as the Swedish-Finnish lines were compressed from three sides. What began as a tactical engagement devolved into a slaughter. Armfeldt’s infantry held their ground with grim determination, but by the evening of February 19, 1714, the Swedish army had been decimated. Approximately 3,000 Swedish and Finnish soldiers lay dead on the fields of Napue, while the Russians suffered roughly 1,500 casualties. Armfeldt and the remnants of his cavalry managed to retreat toward the north, but for all intents and purposes, the organized military defense of Finland had ceased to exist.

Why It Mattered

The Battle of Napue was the decisive turning point that allowed the Tsardom of Russia to consolidate its grip on Finland. With Armfeldt’s army broken, there was no remaining force capable of contesting the Russian occupation. This led directly to one of the darkest chapters in Finnish history, known as the “Great Wrath” (Isoviha).

Between 1714 and 1721, Finland remained under Russian military occupation. The period was characterized by extreme hardship, as the occupying forces engaged in widespread scorched-earth tactics, mass deportations of civilians to Russia for forced labor, and the systematic looting of Finnish villages. The population of Ostrobothnia, in particular, was devastated by the occupation, with many families fleeing across the Gulf of Bothnia to the Swedish mainland.

On a broader geopolitical scale, the victory at Napue confirmed Russia’s emergence as the new Great Power of the North. The Swedish Empire was effectively reduced to a second-rate power, unable to protect its trans-Baltic provinces. The Treaty of Nystad, signed on August 30, 1721, eventually ended the war, but the territorial and psychological scars of the conflict remained. Sweden was forced to cede Livonia, Estonia, Ingria, and parts of Karelia to Russia, signaling the permanent end of the Swedish “Stormaktstiden” (Age of Greatness).

Lasting Legacy

In the cultural memory of Finland, the Battle of Napue remains a symbol of sacrifice and the beginning of a national trauma that helped forge a distinct identity. While the soldiers fought under the Swedish crown, the heavy toll on the local Finnish levies meant that the grief was deeply provincial. In Isokyrö, the memory of February 19, 1714, is preserved by the Napue Monument, erected in 1920 to honor the fallen. The site serves as a reminder of the vulnerability of small nations caught between the ambitions of empires.

The battle also influenced military thought. The failure of the Swedish “Gå-På” tactic at Napue against a more numerically superior and tactically flexible Russian force highlighted the need for modernization in military logistics and maneuverability. The Russian army, conversely, emerged from the Great Northern War as a modernized machine, having learned the lessons of Western European warfare and adapted them to the harsh conditions of the East.

Even as of February 19, 2026, the battle is studied as a classic example of the “pincer” maneuver in winter conditions. It stands as a grim testament to the end of an era-the moment the sun finally set on the Swedish Empire’s dreams of Baltic dominance, leaving behind a scarred but resilient Finland to navigate the long shadow of its eastern neighbor.

Sources

- Great Northern War: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Northern_War

- Battle of Napue: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Napue

- Swedish Empire: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Swedish_Empire

- Tsardom of Russia: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsardom_of_Russia

- Isokyrö: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Isokyr%C3%B6

- Ostrobothnia (historical province): https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostrobothnia_(historical_province)

- The Northern Wars: War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558-1721 by Robert I. Frost (reference lookup recommended).

- Finland in the Great Northern War - National Archives of Finland (reference lookup recommended).