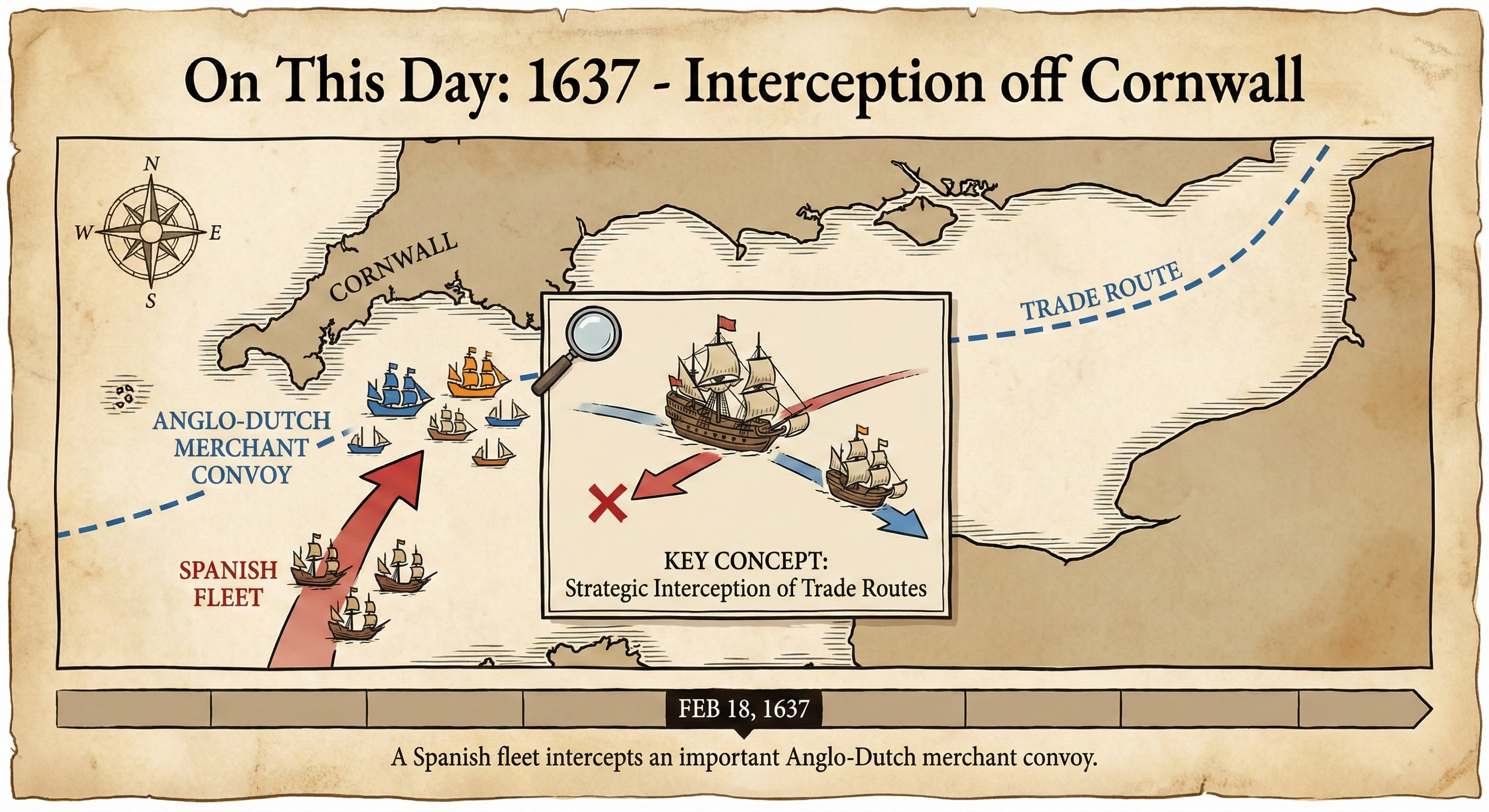

On This Day: 1637 - Off the coast of Cornwall, England, a Spanish fleet intercepts an important Anglo-Dutch merchan

Title: On This Day: 1637 - Off the coast of Cornwall, England, a Spanish fleet intercepts an important Anglo-Dutch merchant convoy Generation date: February 18, 2026 Event date: February 18, 1637

The mist clinging to the jagged granite of Lizard Point on February 18, 1637, did not carry the usual scent of salt and rain; instead, it bore the sharp, acrid stench of black powder. High on the cliffs of Cornwall, a shepherd might have looked out to see a horizon choked with canvas and fire. On the quarterdeck of the San Cristóbal, Admiral Miguel de Horna-a man whose reputation as a scourge of the Narrow Seas was already well-cemented-watched through a spyglass as his Dunkirker squadron closed the gap. To Horna, the sight of forty-four merchant vessels wallowing in the swells was not merely a tactical objective; it was a harvest.

Miles across the churning water, a Dutch merchant captain named Jan Simonszoon likely felt the cold realization of a fatal miscalculation. He was part of a massive convoy, a vital artery of commerce bound for the markets of the Dutch Republic, escorted by what had seemed a sufficient force of six warships. But as the Spanish prows bit into the waves, the math of survival changed. For the English sailors aboard the merchantmen, caught in the crossfire of a war that was technically not their own, the morning was a chaotic blur of splintering oak and the screams of the wounded. This was the Battle off Lizard Point, a moment where the grand geopolitical ambitions of the Spanish Empire and the Dutch Republic collided with devastating consequences for the men caught in between.

The Stakeholders

The confrontation on February 18, 1637, was a violent expression of the Eighty Years’ War, a conflict that had long since transcended a simple rebellion into a global struggle for maritime supremacy. At the heart of the action were the Spanish Dunkirkers. Operating out of the Spanish Netherlands, these were not the lumbering galleons of the Spanish Armada but sleek, aggressive frigates designed for interception and speed. To the Spanish Empire, these privateers and naval squadrons were the most effective tool remaining to puncture the economic vitality of their northern rivals.

The Dutch Republic, meanwhile, was the burgeoning economic engine of Europe. Their stake was existential. The Dutch “Economic Miracle” depended entirely on the unhindered movement of convoys through the English Channel. Each ship lost was not just a blow to a merchant house in Amsterdam; it was a reduction in the tax revenue needed to fund the land armies holding the Spanish at bay in the Low Countries.

The Kingdom of England occupied a precarious and often contradictory position. While King Charles I asserted a “Sovereignty of the Seas,” his actual ability to police his own waters was limited. The Anglo-Dutch convoy consisted of vessels from both nations, highlighting the blurred lines of 17th-century commerce. England wanted the profits of trade without the costs of the war, yet on February 18, 1637, the neutrality of Cornish waters proved to be a paper-thin shield.

Decisions and Constraints

The Spanish victory was not a matter of luck but of calculated aggression and timing. Admiral Miguel de Horna operated under a clear constraint: he was outnumbered in terms of total hulls, but he possessed overwhelming superiority in concentrated firepower and naval discipline. The Spanish fleet consisted of eight powerful warships. Facing them were six Dutch escort warships and a sprawling, disorganized tail of forty-four merchant vessels.

Horna’s decision-making focused on the “head of the snake.” He knew that if he could paralyze the escort, the merchantmen-slow-moving and under-gunned-would become easy prey. On the morning of February 18, 1637, he utilized the wind to cut between the escorts and their charges. This tactical maneuver forced the Dutch warships to fight a defensive action while being unable to shield the entirety of the long convoy line.

The Dutch commanders faced a different set of constraints. Their primary duty was to protect the cargo, yet they were hampered by the varying speeds of the merchant ships. Communication in 1637 was limited to signal flags and lanterns, which often failed in the smoke of battle. When Horna struck, the convoy fractured. Some captains chose to flee toward the Cornish coast, hoping the shallow waters or the proximity to English land would deter the Spanish. It was a gamble that failed for many.

Human Cost and Tradeoffs

The ledger of the battle was written in blood and wreckage. By the time the sun set on February 18, 1637, the Spanish had captured or destroyed three of the six Dutch escort ships. The Galen, a Dutch warship, was sent to the bottom of the Celtic Sea, taking many of its crew with it. The human cost extended far beyond the naval personnel. Of the forty-four merchant vessels, between fourteen and seventeen were captured and towed back toward Dunkirk as prizes of war.

For the sailors aboard those captured ships, the tradeoff for their lives was a grim period of captivity in the Spanish Netherlands. Many were English mariners who found themselves pawns in a Spanish-Dutch chess match. The economic impact was staggering; the loss of twenty ships in a single day represented a massive hit to the Dutch West India Company and various English merchant interests.

There was also a political cost for the Kingdom of England. The fact that such a massive battle could take place within sight of the Cornish coast was a public embarrassment for Charles I. It demonstrated that the English Navy was incapable of protecting its own territorial waters, a realization that would fuel domestic political tensions regarding ship money and naval funding in the years leading up to the English Civil War.

Historical Assessment

The Battle off Lizard Point remains a significant, if often overlooked, chapter in the decline of Spanish maritime power-ironic, given that it was a resounding Spanish victory. It proved that even as the Spanish Empire faced domestic decay and military pressure on multiple fronts, its naval forces in the North Sea remained a lethal and sophisticated threat. On February 18, 1637, Spain demonstrated that it could still dictate the terms of engagement in the Atlantic.

However, the battle also illustrated the long-term futility of the Spanish strategy. While Horna could win tactical victories and seize prizes, the Dutch Republic’s merchant marine was too vast to be bled dry by such raids. The Dutch simply built more ships, refined their convoy systems, and continued to dominate global trade.

Historically, the engagement is a prime example of the “Guerra de Galaro” (War of the Dunkirkers), a precursor to modern commerce raiding. It showed that the control of bottlenecks like the English Channel and the coast of Cornwall was more important than the control of the open ocean. The events of February 18, 1637, serve as a reminder that the sea has always been a space where the boundaries of nations are fluid, and where the decisions of a single admiral can ripple through the economies of entire continents.

Sources

- Eighty Years’ War: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War

- Cornwall: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornwall

- Spanish Empire: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_Empire

- Battle off Lizard Point: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_off_Lizard_Point

- Kingdom of England: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_England

- Dutch Republic: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_Republic

- The Dunkirk Pirates and the Thirty Years’ War, reference lookup recommended.

- Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail, reference lookup recommended.