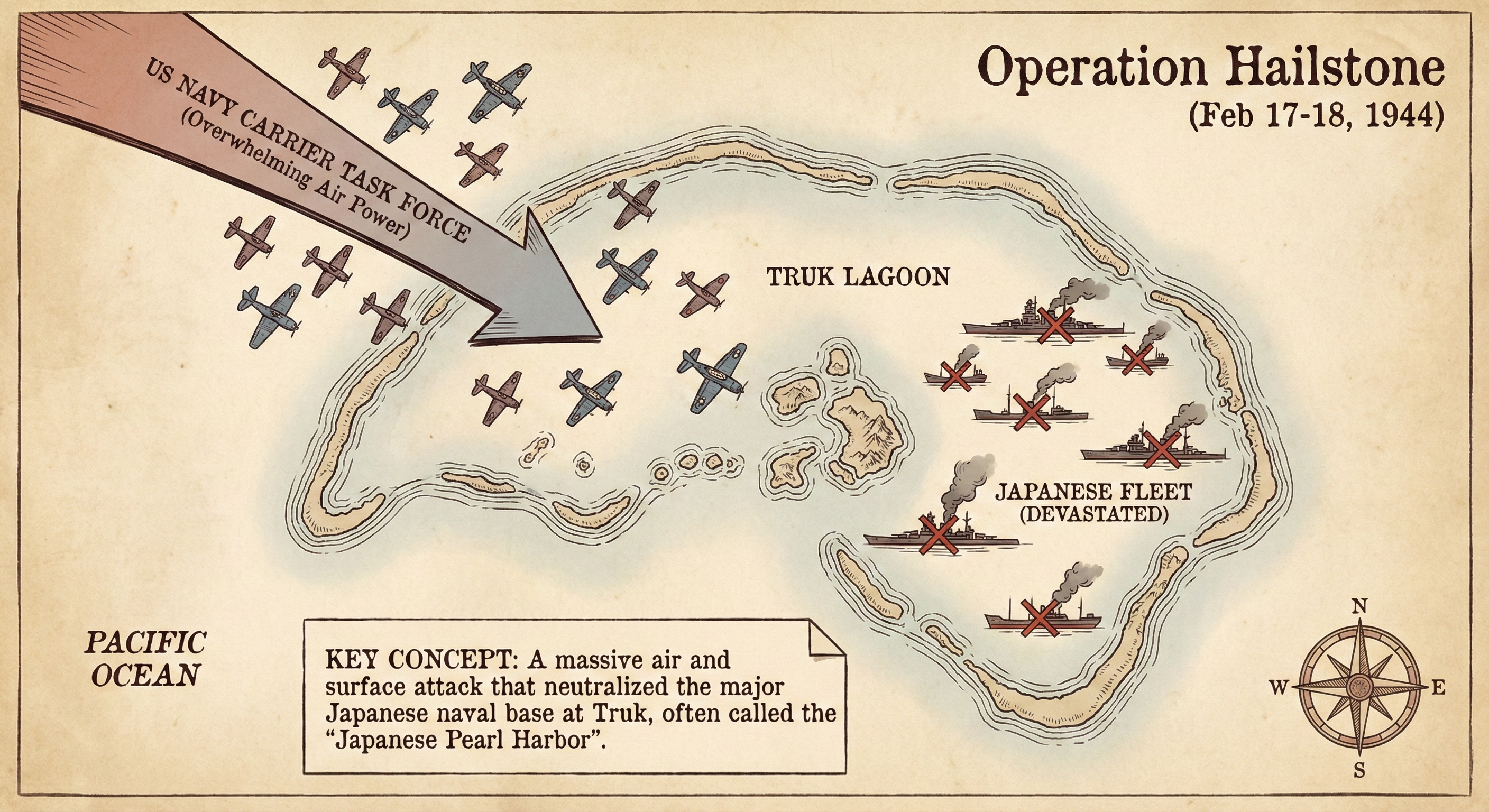

On This Day: 1944 - Operation Hailstone

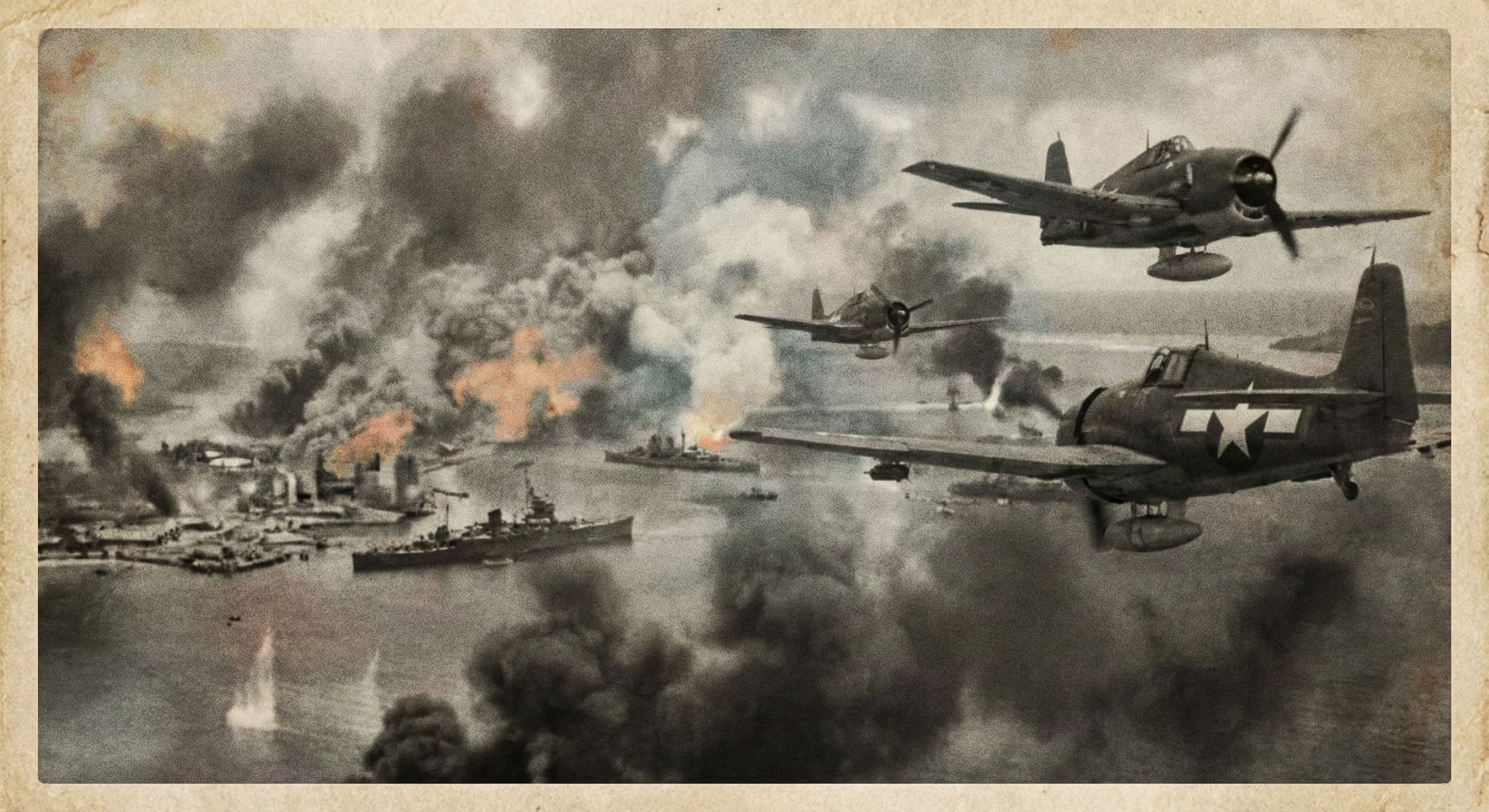

The morning of February 17, 1944, broke with a deceptive stillness over the turquoise waters of Truk Lagoon. For Petty Officer Second Class Toshiro Matsuda, stationed aboard the auxiliary cruiser Aikoku Maru, the dawn light usually signaled the start of a routine day in the “Gibraltar of the Pacific.” Truk was considered an impregnable fortress, the jewel of the Mandated Territories, and the primary forward operating base for the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet. Matsuda and his shipmates felt a sense of security shielded by the towering volcanic peaks and the sprawling coral reefs that ringed the lagoon.

Miles away, Lieutenant Commander Robert “Killer” Kane sat in the cockpit of his F6F Hellcat on the flight deck of the USS Enterprise. As the massive carrier turned into the wind, the objective was clear: neutralize the threat of Truk to protect the upcoming invasion of Eniwetok. For the American aviators, this was the chance to settle a score that had lingered since the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The mission, designated Operation Hailstone, was not merely a tactical maneuver; it was a psychological blow aimed at the heart of Japanese naval prestige. When the first wave of 72 fighters roared off the decks of Task Force 58, the air over the Caroline Islands was about to become a furnace.

The Stakeholders

The primary actors in this theater represented the pinnacle of naval power in early 1944. On the American side, Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance and Rear Admiral Marc Mitscher commanded Task Force 58, a terrifyingly efficient assembly of nine aircraft carriers, six battleships, and dozens of support vessels. For the United States, the stakeholders included the thousands of young pilots and sailors whose lives depended on the suppression of Japanese airpower before the scheduled landings on Eniwetok on February 18, 1944.

On the Japanese side, the stakeholders were led by Admiral Mineichi Koga, who had succeeded the late Isoroku Yamamoto. However, Koga had already sensed the shifting tides of the war. By February 10, 1944, he had ordered the withdrawal of the Combined Fleet’s heavy capital ships, including the super-battleship Musashi, to the safer waters of Palau. This left behind a secondary tier of stakeholders: the crews of approximately 50 merchant ships and smaller naval vessels, and the thousands of army and navy personnel garrisoned on the islands of Dublon, Eten, and Moen.

Another group, often overlooked in the military histories of Operation Hailstone, was the indigenous Chuukese population. For centuries, these islands had been their home, yet by February 1944, they were trapped between two warring empires. Their ancestral lands had been transformed into runways and fuel depots, and the onset of the American bombardment turned their peaceful lagoon into a graveyard of twisted metal and burning oil.

Decisions and Constraints

The execution of Operation Hailstone was born from a rigorous debate within the American high command. The central constraint was time. The Battle of Eniwetok was slated to begin on February 18, 1944, and Truk sat within striking distance of the invasion route. Admiral Chester Nimitz faced a difficult choice: bypass the base and risk a flank attack, or commit the bulk of his carrier strength to a risky strike against a heavily defended “unsinkable aircraft carrier.” The decision to strike was finalized in early February 1944, prioritizing the destruction of Japanese air assets and shipping over a land invasion of Truk itself.

For the Japanese, the constraints were largely logistical and intelligence-based. Although a single American PB4Y-1 Liberator had performed a daring high-altitude reconnaissance flight over the lagoon on February 4, 1944, the Japanese command failed to fully grasp the immediacy of the threat. While they had moved the most valuable warships out of harm’s way, they failed to evacuate the merchant vessels and fuel tankers that were the lifeblood of their Pacific logistics. The decision to keep these “soft targets” in the lagoon proved catastrophic.

Tactically, Admiral Mitscher made the decisive choice to launch a pre-dawn fighter sweep on February 17, 1944. This move was intended to achieve air superiority before the slower torpedo bombers and dive bombers arrived. The constraint of limited deck space on the carriers meant that the timing of these waves had to be choreographed with mathematical precision. Any delay would allow Japanese Zeros to get airborne and intercept the vulnerable bombers.

Human Cost and Tradeoffs

The human cost of the two-day operation was staggering. On the morning of February 17, 1944, the Aikoku Maru was struck by a torpedo from an American plane. The resulting explosion was so violent that it instantly killed everyone on board and actually consumed the attacking American aircraft in the fireball. This single event epitomized the brutal tradeoffs of the engagement: the Americans traded a single plane and two crewmen for a 10,000-ton ship and hundreds of Japanese lives.

By the time the operation concluded on February 18, 1944, more than 250,000 tons of shipping lay at the bottom of the lagoon. This included the loss of roughly 40 ships and over 250 aircraft. For the Japanese, the casualties exceeded 4,500 personnel killed, many of them trapped in the hulls of sinking merchant vessels. The Americans lost 40 men and 25 aircraft, a relatively low number given the scale of the victory, but a significant loss for the families of those pilots who vanished into the Pacific.

For the Chuukese people, the cost was measured in the destruction of their environment and the trauma of relentless bombardment. The “tradeoff” for the American forces was the safety of the Eniwetok invasion force. By neutralizing Truk, the US avoided a potentially bloody amphibious assault on the island itself, which would have likely cost thousands of American lives. Instead, they “leapfrogged” the base, leaving the remaining Japanese garrison to wither away from starvation and disease for the remainder of the war.

Historical Assessment

Operation Hailstone stands as a pivotal moment in the transition of naval warfare. It demonstrated that the carrier task force had replaced the battleship as the primary instrument of national power. The destruction wrought on February 17, 1944, effectively ended Truk’s utility as a strategic threat. The base was not captured but rendered irrelevant, a textbook example of the “island-hopping” strategy that defined the Pacific campaign.

In the decades following the conflict, the lagoon became a site of dual significance. To the Japanese families of the fallen, it remains a vast underwater cemetery. To the scientific and diving communities, the wrecks became an accidental marine sanctuary and a time capsule of 1940s naval technology. By February 17, 2026, the sunken ships-now known as the “Ghost Fleet of Truk Lagoon”-have become one of the most famous wreck-diving destinations in the world, though they remain fragile and subject to the slow decay of seawater and time.

Historians often refer to Operation Hailstone as “the Japanese Pearl Harbor,” though the comparison is technically inverted. At Pearl Harbor, the Japanese hit a stationary fleet but failed to destroy the carriers or the fuel farms. At Truk, the Americans succeeded in both, effectively breaking the back of the Japanese merchant marine and isolating the remaining outposts in the Central Pacific. The success of the operation ensured that the Battle of Eniwetok could proceed without interference, accelerating the Allied advance toward the Japanese home islands and shortening the duration of the war.

Sources

- Operation Hailstone: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Hailstone

- Truk Lagoon: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Truk_Lagoon

- Battle of Eniwetok: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Eniwetok

- The Barrier and the Javelin: Japanese and Allied Pacific Strategies, February to June 1942, reference lookup recommended.

- Combined Fleet Decoded: The Secret History of American Intelligence and the Japanese Navy, reference lookup recommended.

- The Second World War, Winston Churchill, reference lookup recommended.