On This Day: 1940 - Altmark incident: The German tanker Altmark is boarded by sailors from the British destroyer HM

Title: On This Day: 1940 - Altmark incident: The German tanker Altmark is boarded by sailors from the British destroyer HM Generation date: February 16, 2026 Event date: February 16, 1940 Style profile: Narrative Chronicle

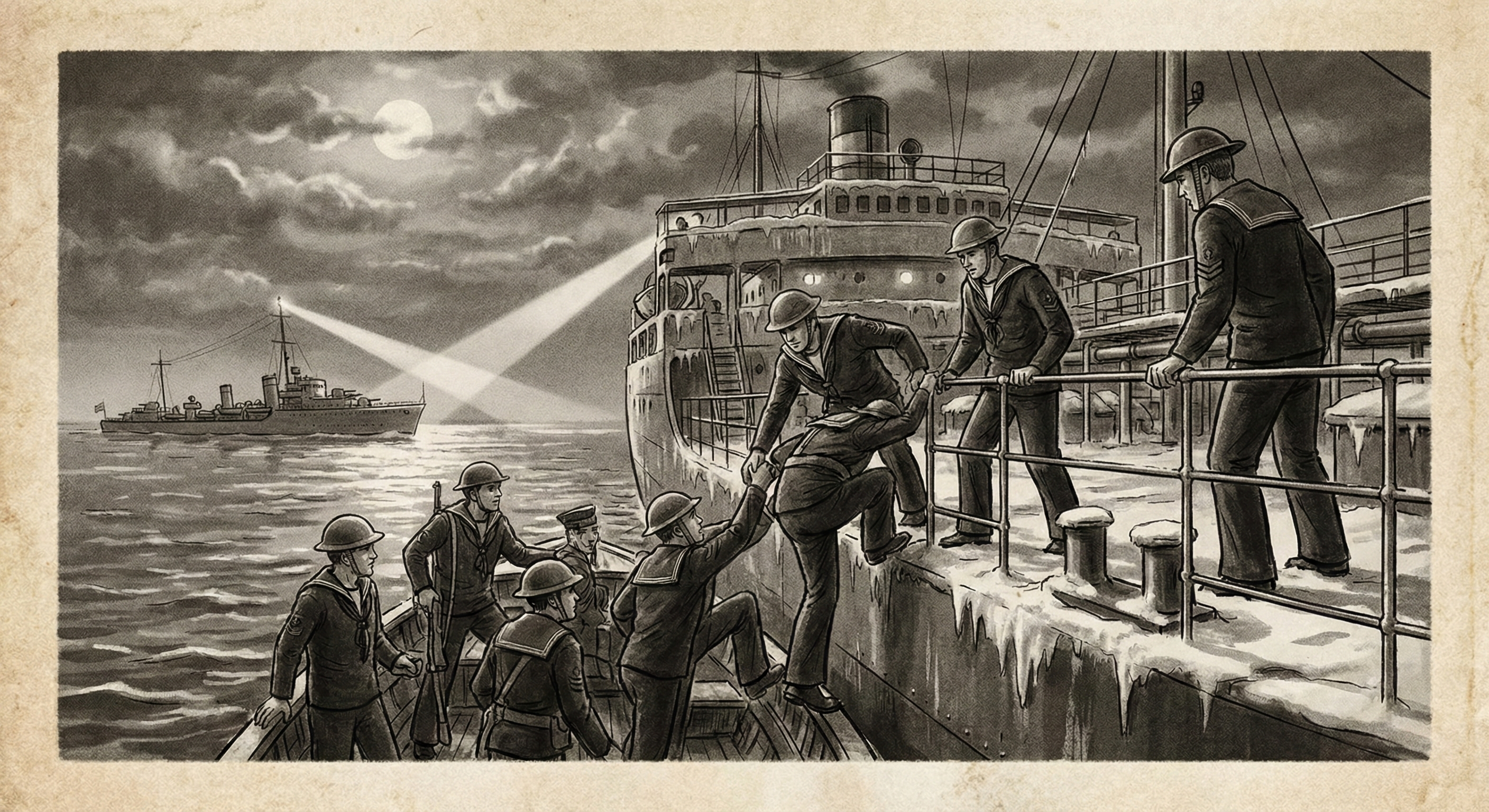

The freezing mist clung to the sheer, jagged cliffs of the Jøssingfjord on the evening of February 16, 1940. This narrow inlet on the southwestern coast of Norway, usually a sanctuary of silence and deep water, became the stage for a desperate game of maritime chess. The German tanker Altmark, a massive vessel of some 12,000 tons, sat huddled against the ice-rimmed rocks, its hull casting a long shadow over the dark Norwegian waters. On its deck, the German crew kept a nervous watch, aware that the Royal Navy was prowling just outside the territorial limit. Beneath the hatches, in the cramped, airless storage holds and ammunition lockers, nearly 300 British merchant sailors-prisoners of war-listened to the rhythmic thrum of the ship’s engines and the terrifying silence of their captors. They had been at sea for months, the human trophies of a commerce raider that had already met its end. As the moon rose over the fjord, the silhouette of a British destroyer, the HMS Cossack, cut through the frigid air, its prow slicing the water with the intent of a predator that had finally cornered its prey.

Historical Context

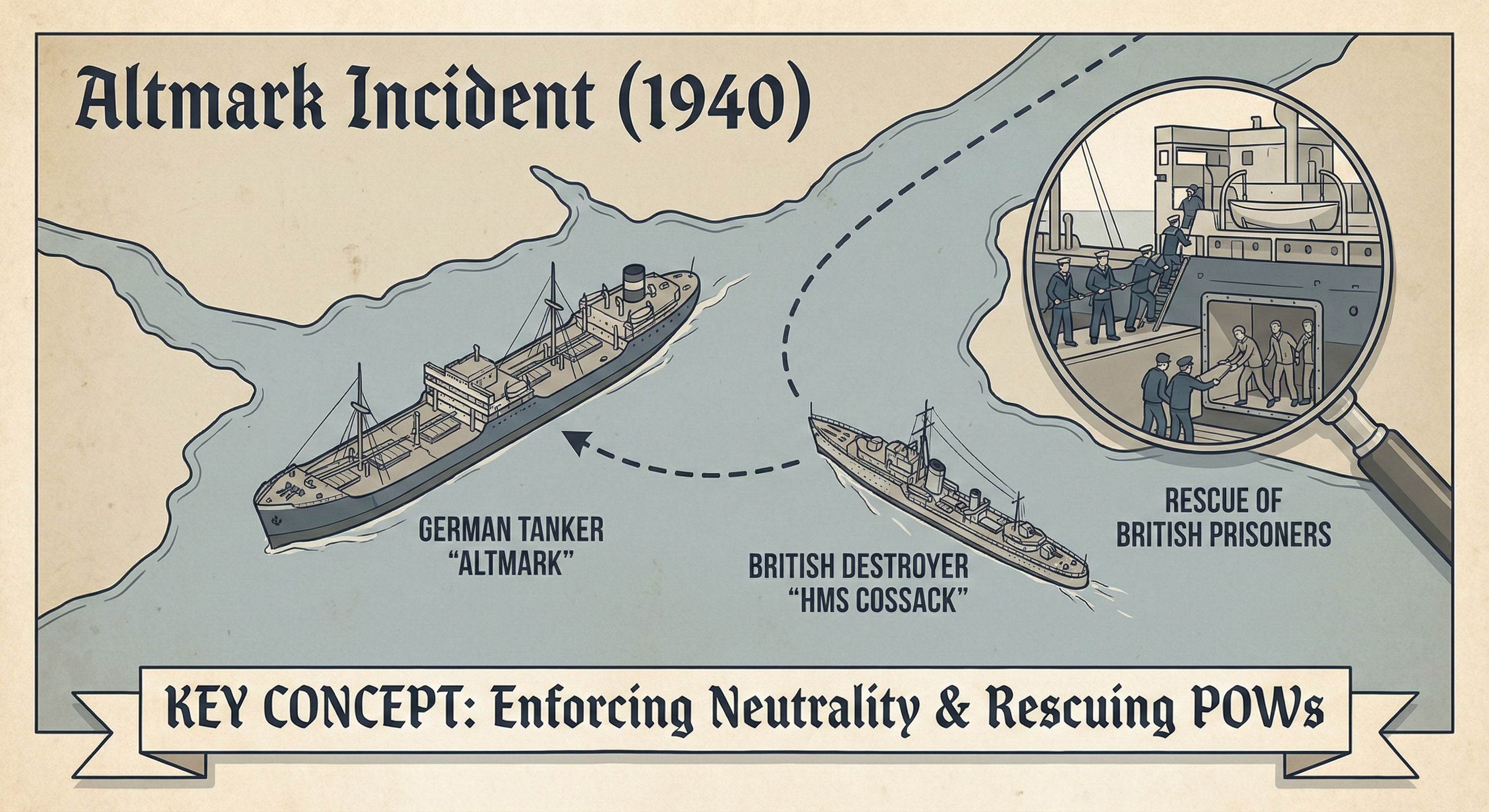

The winter of 1939 and the early months of 1940 are often characterized by the term “Phoney War,” a period of relative stalemate on the Western Front following the invasion of Poland. However, at sea, the conflict was already burning with a white-hot intensity. The German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee had spent the late months of 1939 terrorizing Allied shipping in the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans. By the time the Graf Spee was scuttled following the Battle of the River Plate on December 17, 1939, it had sunk nine merchant vessels. But the battleship was not alone; it had been supported by the Altmark, a specialized tanker and supply ship commanded by Captain Heinrich Dau.

When the Graf Spee met its end off the coast of Uruguay, the Altmark became a ghost ship. It carried 299 captured crewmen from the ships the Graf Spee had destroyed. Captain Dau’s mission was to navigate the British-controlled Atlantic and return these prisoners and his vessel to Germany. For nine weeks, the Altmark played a deadly game of hide-and-seek, eventually looping far north around the British Isles to enter the neutral waters of Norway.

The Norwegian government found itself in a diplomatic vice. Under international law-specifically the Hague Convention-a neutral power could allow a belligerent’s warships or auxiliary vessels to pass through its territorial waters, provided they did not stop for more than 24 hours and did not use the neutral territory as a base for naval operations. The Norwegian authorities had inspected the Altmark twice during its passage down the coast in mid-February 1940. However, the inspections were cursory; the German captain insisted no prisoners were aboard, and the Norwegian officers, wary of provoking Germany or Britain, chose not to conduct a thorough search of the locked holds. This lack of diligence infuriated Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, who viewed the Altmark’s presence in neutral waters as a flagrant abuse of international law by the Third Reich.

What Happened

On February 16, 1940, the British Admiralty’s patience evaporated. Churchill issued a direct order to Captain Philip Vian of the destroyer HMS Cossack: enter Norwegian waters, board the Altmark, and liberate the prisoners, regardless of Norwegian protests. The Cossack intercepted the Altmark in the Jøssingfjord, where the German ship had sought refuge. Two Norwegian torpedo boats, the Kjell and the Skarv, stood by, their commanders protesting the British violation of their neutrality. Captain Vian, acting under the authority of the British government, ignored the protests, famously inviting the Norwegian officers to join the boarding party to ensure the prisoners were treated fairly. They declined.

As the HMS Cossack drew alongside the Altmark, the German tanker attempted to ram the smaller, more agile destroyer. The Altmark ran aground on the rocks of the fjord, its stern lodged firmly in the ice and silt. In a scene reminiscent of the Age of Sail, British sailors leaped from the Cossack onto the decks of the tanker. This was one of the last instances of a traditional boarding action in the history of the Royal Navy. Armed with rifles and bayonets-and in some accounts, even cutlasses-the British sailors engaged the German crew in hand-to-hand combat.

The skirmish was brief but violent. Seven German sailors were killed and several wounded, while the British suffered only minor casualties. In the chaos, the boarding party moved toward the hatches. According to naval legend, when the British sailors broke the locks and looked down into the dark holds, one of them called out, “Any Britishers down there?” When the prisoners roared back in affirmation, the sailor shouted the phrase that would soon echo across the United Kingdom: “Come up, then! The Navy’s here!” One by one, the 299 men, many of whom had not seen sunlight for weeks, scrambled onto the deck and were transferred to the Cossack. By midnight, the destroyer was steaming back toward Scotland, leaving the grounded Altmark and a shocked Norwegian navy behind.

Why It Mattered

The immediate impact of the Altmark incident was a massive surge in British morale. In February 1940, the public was starved for good news. The liberation of the 299 prisoners was a clean, heroic victory that showcased the Royal Navy’s reach and resolve. “The Navy’s here!” became a rallying cry throughout the British Empire, appearing on propaganda posters and in newsreels as a symbol of defiance against the German blockade.

However, the diplomatic and strategic consequences were far darker. For Norway, the incident was a catastrophe. It proved that neither Germany nor Britain truly respected Norwegian neutrality if it conflicted with their strategic interests. The British had physically violated Norwegian waters to seize the ship, and the Germans had used those same waters to transport prisoners of war-both arguably violations of the spirit of neutrality.

For Adolf Hitler, the Altmark incident was the final proof that the British would eventually seize Norway to cut off the supply of Swedish iron ore to Germany. The German High Command had already been drafting plans for an invasion of Scandinavia, but the events of February 16, 1940, accelerated their timeline. Hitler was incensed by what he perceived as Norwegian complicity or weakness in allowing the British to board a German vessel in their own backyard. On February 21, 1940, just five days after the boarding, Hitler ordered the intensification of planning for Operation Weserübung-the invasion of Denmark and Norway. This move shifted the war from its “phoney” phase into a total conflict that would soon engulf the whole of Western Europe.

Lasting Legacy

The Altmark incident remains a pivotal case study in international maritime law and the ethics of neutrality during wartime. It illustrated the fragility of small nations caught between warring superpowers. In Norway, the name of the fjord-Jøssingfjord-eventually gave birth to the term “Jøssing.” Initially intended by the pro-Nazi Quisling regime as a derogatory term for pro-British or anti-Nazi Norwegians, it was proudly adopted by the Norwegian resistance. To be a “Jøssing” meant to be a patriot who refused to bow to German occupation.

The boarding of the Altmark also marked a transition in the character of the Royal Navy. While it was a moment of traditional “Nelsonian” daring, it occurred on the cusp of a technological revolution that would see the end of such close-quarters naval combat. Captain Philip Vian, who led the raid, would go on to become one of the most distinguished admirals of the war, playing a key role in the hunt for the Bismarck in May 1941 and the D-Day landings in June 1944.

Even on February 16, 2026, the legacy of the incident is felt in the way modern navies navigate the complexities of territorial waters and the protection of merchant shipping. The phrase “The Navy’s here” persists in naval lore as a shorthand for the protective presence of a fleet during times of crisis. The Altmark itself was eventually refloated and renamed the Uckermark, only to be destroyed by an accidental explosion in Yokohama, Japan, on November 30, 1942. Its end was far less dramatic than the night in the Jøssingfjord when, for a few brief hours, the world watched as a narrow Norwegian inlet became the focal point of a global struggle for survival.

Sources

- World War II: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II

- Altmark incident: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Altmark_incident

- German tanker Altmark: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/German_tanker_Altmark

- Destroyer: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Destroyer

- HMS Cossack: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Cossack

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War: Volume II, Their Finest Hour. Houghton Mifflin (Reference lookup recommended).

- Frischauer, Willi, and Robert Jackson. The Navy’s Here! The Altmark Affair. Gollancz, 1955 (Reference lookup recommended).

- National Archives of Norway (Arkivverket), Records on the Jøssingfjord Incident (Reference lookup recommended).