On This Day: 1898 - The battleship USS Maine explodes and sinks in Havana harbor in Cuba, killing about 274 of the

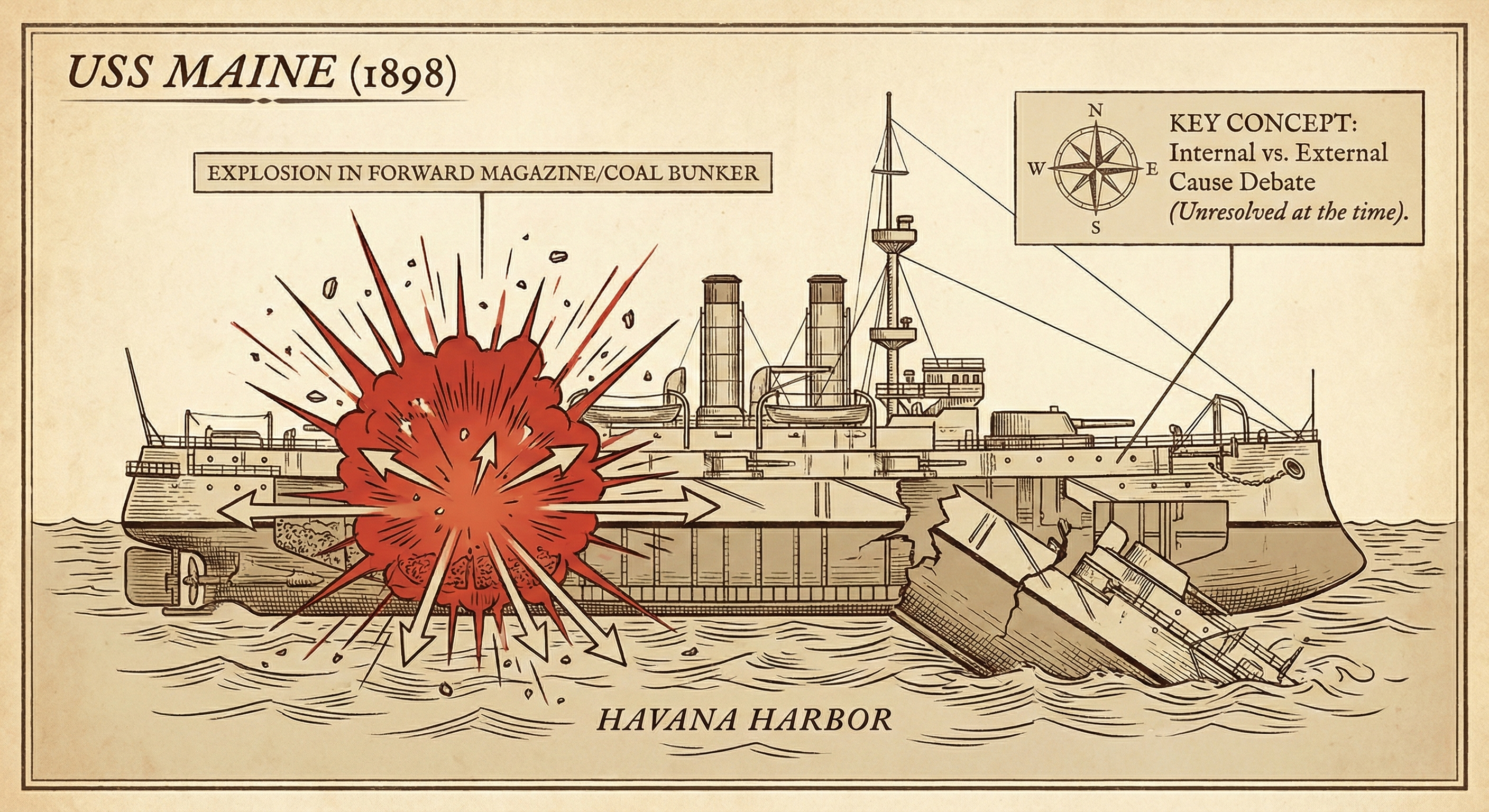

At 9:40 PM on February 15, 1898, the evening silence of Havana Harbor was shattered by a massive explosion that ripped through the forward section of the USS Maine. The blast was so violent that it lifted the five-ton forward turret into the air before the ship began a rapid descent into the mud of the harbor floor. Out of a crew of roughly 354 men, approximately 274 perished, most trapped in the lower berths as the vessel flooded. This catastrophic event did more than destroy a second-class battleship; it ignited a fervor for war in the American public and fundamentally shifted the geopolitical trajectory of the Western Hemisphere. The sinking served as the immediate catalyst for the Spanish-American War, transforming the United States from a continental power into an overseas empire.

Fast Background

The presence of the USS Maine in Havana during early 1898 was the result of years of escalating tension between the United States and Spain. Cuba, a colony that had been under Spanish rule for centuries, was embroiled in its final and most brutal war for independence, which began in February 1895. Under the command of General Valeriano Weyler, the Spanish military implemented a “reconcentration” policy, forcing Cuban civilians into fortified towns to prevent them from aiding the rebels. These camps became breeding grounds for disease and starvation, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands.

In the United States, the “Yellow Press”-led by Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal-sensationalized these atrocities, fueling a wave of public sympathy for the Cuban “insurrectos.” While President William McKinley sought a diplomatic resolution to avoid military intervention, the situation grew increasingly volatile. In January 1898, riots broke out in Havana, led by Spanish loyalists who opposed any concessions to the rebels.

To protect American lives and property, and to signal American resolve, the USS Maine was dispatched to Havana. Arriving on January 25, 1898, the ship was ostensibly on a “friendly” visit, though its presence was clearly a tactical warning. For three weeks, the ship sat anchored in the harbor, a floating fortress of white steel that represented the growing shadow of American influence over Spanish Caribbean interests.

Timeline of Key Moments

- February 1895: The Cuban War of Independence begins, sparking renewed American interest in the Caribbean and threatening U.S. sugar investments on the island.

- January 25, 1898: The USS Maine arrives in Havana Harbor. Despite the underlying tension, Captain Charles Sigsbee and his officers are initially treated with formal courtesy by Spanish officials.

- February 9, 1898: The New York Journal publishes the “De Lôme Letter,” a private missive from the Spanish Minister to the United States that criticized President McKinley as “weak” and a “bidder for the admiration of the crowd.” The leak infuriates the American public.

- February 15, 1898 (9:40 PM): A massive explosion occurs in the forward section of the USS Maine. The ship sinks almost instantly. Survivors are rescued by the nearby Spanish steamer City of Washington and the American ship Ward.

- February 16, 1898: Captain Sigsbee sends a telegram to Washington urging “public opinion should be suspended until further report,” but the American press immediately blames Spain for the disaster.

- March 21, 1898: The U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry, known as the Sampson Board, concludes that the ship was destroyed by a submerged mine which subsequently ignited the forward magazines. No specific party is named as responsible, but the implication points toward Spanish agents.

- April 11, 1898: President McKinley asks Congress for authority to intervene in Cuba to end the civil war and protect American interests.

- April 25, 1898: The United States formally declares war on Spain, backdating the start of the war to April 21.

Inflection Point

The destruction of the USS Maine represents one of the most significant inflection points in American diplomatic history. Before February 15, 1898, the United States was a nation debating the merits of expansionism versus traditional isolationism. After the explosion, the debate was effectively silenced by a wave of jingoistic nationalism. The rallying cry “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!” became a cultural phenomenon, moving the center of political gravity toward military action.

What made this moment an inflection point was not merely the loss of the ship, but the manner in which the loss was interpreted by the media and the government. The explosion happened during a transition in information technology; telegraphs allowed news to travel within hours, and high-speed rotary presses allowed for massive circulations of daily newspapers. Hearst famously told an illustrator, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” The Maine provided the ultimate “picture.” By framing the disaster as a deliberate act of Spanish treachery rather than a possible accident, the press stripped McKinley of his diplomatic maneuvering room. The sinking of the Maine transformed a regional colonial conflict into a global crusade for American “honor,” marking the definitive end of the post-Civil War era of internal focus and the beginning of the United States as a proactive global policeman.

What Followed

The ensuing Spanish-American War lasted less than four months but yielded massive territorial gains for the United States. Following the decisive naval victories at Manila Bay in the Philippines on May 1, 1898, and at Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898, Spain was forced to the negotiating table. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed. In the settlement, Spain relinquished all claim to Cuba and ceded Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands to the United States in exchange for $20 million.

The aftermath of the sinking also sparked a century-long forensic debate. In 1911, the wreck of the Maine was raised within a cofferdam so that a second board of inquiry could examine the hull. This board reaffirmed the 1898 finding that an external explosion was the cause. However, on January 1, 1976, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover published a detailed modern technical analysis of the disaster. His team of engineers concluded that the most likely cause was not a mine, but an internal fire in a coal bunker located adjacent to a reserve magazine. This phenomenon-spontaneous combustion of bituminous coal-was a known hazard in ships of that era.

Despite these later scientific findings, the historical impact of the 1898 interpretation remains unchanged. The event accelerated the annexation of Hawaii in July 1898 and eventually led to the 1901 Platt Amendment, which allowed the United States to intervene militarily in Cuba to “protect” its independence. The sinking of the USS Maine on February 15, 1898, remains the quintessential example of how a single catastrophic event, filtered through the lens of a sensationalist media, can steer a nation into a war that fundamentally alters the map of the world.

Sources

- USS Maine (1890): https://wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Maine_(1890)

- Havana: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Havana

- Cuba: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuba

- United States: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States

- Spanish-American War: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish%E2%80%93American_War

- Spain: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Spain

- Rickover, H. G. (1976). How the Battleship Maine was Destroyed. Naval History Division, Department of the Navy. (Reference lookup recommended)

- Musicant, Ivan. (1998). Empire by Default: The Spanish-American War and the Dawn of the American Century. Henry Holt and Company. (Reference lookup recommended)

- The National Archives: Records of the U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry into the Sinking of the USS Maine, 1898. (Reference lookup recommended)