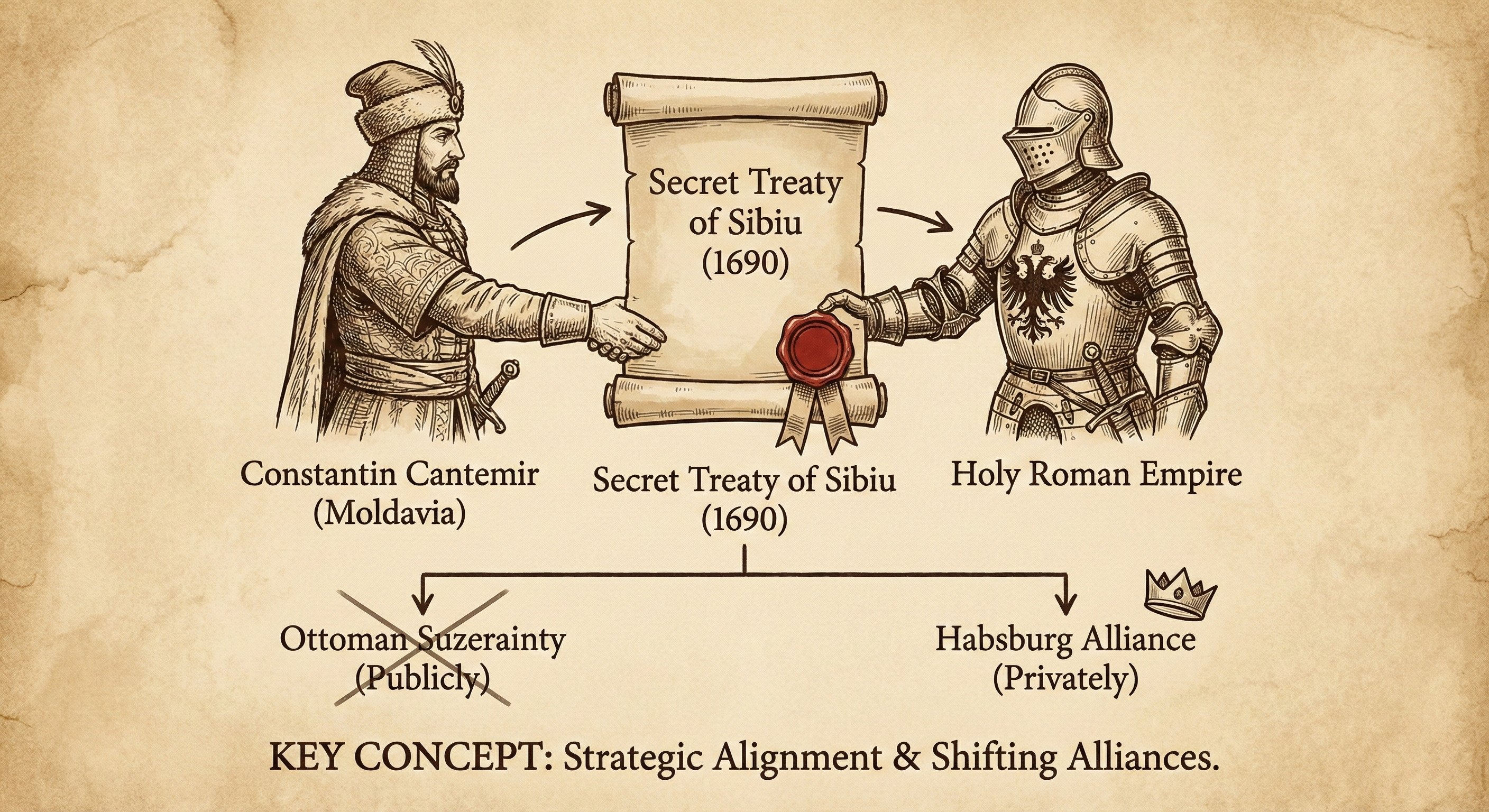

On This Day: 1690 - Constantin Cantemir, Prince of Moldavia, and the Holy Roman Empire sign a secret treaty in Sibi

What People Commonly Get Wrong

A persistent narrative in Eastern European historiography paints Constantin Cantemir as a blunt, unlettered soldier who ascended to the throne of Moldavia simply because he was a safe, manageable choice for the Ottoman Empire. In this version of history, Cantemir is viewed as a loyalist to the Sublime Porte, a prince who lacked the sophisticated political vision of his more famous son, the scholar-king Dimitrie Cantemir. Popular accounts often suggest that the older Cantemir was merely a placeholder, a man of limited ambition who spent his reign from June 15, 1685, until his death on March 27, 1693, simply trying to keep his head attached to his shoulders while the Great Turkish War raged around him.

This characterization suggests that any move toward the West during this period was the result of accidents or external coercion rather than deliberate strategy. It assumes that because Cantemir was a veteran of the Ottoman military machine, his allegiance was singular and his intellect was confined to the battlefield. The image of the “illiterate prince” became a convenient foil for later Enlightenment biographers who wanted to emphasize the intellectual leap made by the next generation of the Cantemir family.

However, the reality of the geopolitical landscape in the late 17th century demands a more nuanced view. The idea that Constantin Cantemir was a passive observer of history is contradicted by the intricate, dangerous diplomatic web he wove. Far from being a simple puppet of Istanbul, he was an architect of survival. The common misconception fails to account for the Prince’s ability to navigate the conflicting interests of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the rising power of the Habsburgs, and the entrenched authority of the Sultan. He was not a man of blind loyalty; he was a man of calculated risks who understood that the winds of power were shifting toward Central Europe.

What the Evidence Shows

The documentary evidence surrounding the events of February 15, 1690, provides a starkly different picture of Constantin Cantemir’s reign. On that date, in the Transylvanian city of Sibiu, a secret treaty was formalized between the Prince of Moldavia and the Holy Roman Empire, represented by the House of Habsburg. This was not the act of a submissive Ottoman vassal, but a bold pivot toward the Western powers that were then dismantling Ottoman hegemony in the wake of the failed Siege of Vienna in 1683.

The Treaty of Sibiu was the culmination of clandestine negotiations conducted under the constant threat of Ottoman discovery. The text of the agreement stipulated that Moldavia would provide logistical support, intelligence, and a pathway for Habsburg military operations against Ottoman forces. This was a direct violation of the ahdnâmes (treaties) that bound Moldavia to the Ottoman Empire. While Cantemir publicly maintained his role as a faithful servant of the Sultan-even participating in campaigns against the Poles-the private records of the Habsburg chancellery show he was simultaneously ensuring that his principality would have a seat at the table should the Christian coalition prevail.

Furthermore, the logistical details of the 1690 agreement show a high level of administrative foresight. Cantemir promised to facilitate the movement of imperial troops and to provide provisions, a move that required a sophisticated understanding of both military geography and economic resource management. The very fact that these negotiations took place in Sibiu, a vital Saxon stronghold within the Habsburg-controlled Principality of Transylvania, highlights the Prince’s reach. He was engaging in high-stakes “triangular diplomacy,” playing the Habsburgs against the Ottomans while keeping an eye on the territorial ambitions of King Jan III Sobieski of Poland.

Main Turning Points

The journey to the February 15, 1690, treaty began with the seismic shift in European power that occurred on September 12, 1683. The defeat of the Ottoman army at the gates of Vienna shattered the aura of Ottoman invincibility. For a border state like Moldavia, this created a terrifying but opportunistic vacuum. Constantin Cantemir took the throne in 1685, precisely when the “Holy League”-comprising the Holy Roman Empire, Poland, and Venice-was beginning its counter-offensive.

A major turning point occurred in 1686 when Polish forces invaded Moldavia. Cantemir was forced to retreat with the Ottomans, but he observed the inability of the Sultan’s forces to decisively expel the Polish King. This demonstrated to the Moldavian court that the old order was failing. By 1687, the Habsburgs had secured significant victories in Hungary and were looking toward the principalities of the Danube. Cantemir recognized that if he did not reach an accommodation with the House of Habsburg, Moldavia risked being treated as a conquered Ottoman province rather than a sovereign ally.

The specific timing of the treaty in early 1690 was influenced by the shifting fortunes of the Great Turkish War. The year 1689 had seen the Habsburgs capture Belgrade and push deep into the Balkans. However, an Ottoman counter-attack was brewing. Cantemir chose February 15, 1690, as the moment to formalize his secret alliance, likely seeking insurance against the impending violence of the spring campaign season. The secret nature of the document was paramount; if a copy had reached Istanbul, the execution of the Prince and the devastation of the Moldavian capital at Iași would have been certain. This necessitated a level of operational security that involved trusted envoys traveling through the treacherous Carpathian passes to meet imperial representatives in Sibiu.

What Changed Afterward

The immediate aftermath of the Treaty of Sibiu did not result in an overt revolution. Constantin Cantemir was a realist; he knew that a premature declaration of independence would lead to the total destruction of his land. Instead, the treaty created a “shadow policy” in Moldavia. On the surface, the Prince continued to pay his tributes and provide soldiers to the Sultan, but beneath the surface, the infrastructure for a pro-Western alignment was being built.

The most significant long-term change was the shift in the political consciousness of the Moldavian elite. The 1690 treaty established a precedent for the “Europeanization” of Moldavian foreign policy. It proved that the principality could seek protectors other than the Sultan or the King of Poland. This strategic DNA was passed down to his sons, Antioh and Dimitrie. When Dimitrie Cantemir signed the Treaty of Lutsk with Peter the Great of Russia on April 13, 1711, he was not innovating out of thin air; he was following the blueprint of secret, sovereign diplomacy established by his father in Sibiu.

However, the Ottomans were not entirely blind to the shifting loyalties of their Danubian vassals. The suspicion engendered by the secret maneuverings of princes like Constantin Cantemir eventually led the Ottoman Empire to lose faith in local dynasties. Following the 1711 defection of Dimitrie Cantemir, the Ottomans inaugurated the “Phanariote era,” wherein the princes of Moldavia and Wallachia were no longer chosen from local boyars but were instead appointed from the Greek families of the Phanar district in Istanbul. Thus, the secret treaty of February 15, 1690, while a masterpiece of survival for the Cantemir family in the short term, contributed to a broader geopolitical distrust that would eventually cost the Moldavian nobility their right to rule themselves for over a century. The legacy of that day in Sibiu remains a testament to the brutal complexities of being a small state wedged between three collapsing and expanding empires.

Sources

- Constantin Cantemir: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Constantin_Cantemir

- Moldavia: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Moldavia

- Holy Roman Empire: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Roman_Empire

- Sibiu: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Sibiu

- House of Habsburg: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Habsburg

- Ottoman Empire: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_Empire

- The Cantemirs: The History of a Family in the 17th and 18th Centuries (Reference lookup recommended)

- The Great Turkish War and the Danubian Principalities: 1683-1699 (Reference lookup recommended)

- Diplomatic Correspondence of the Habsburg Chancellery, 1690-1695 (Reference lookup recommended)