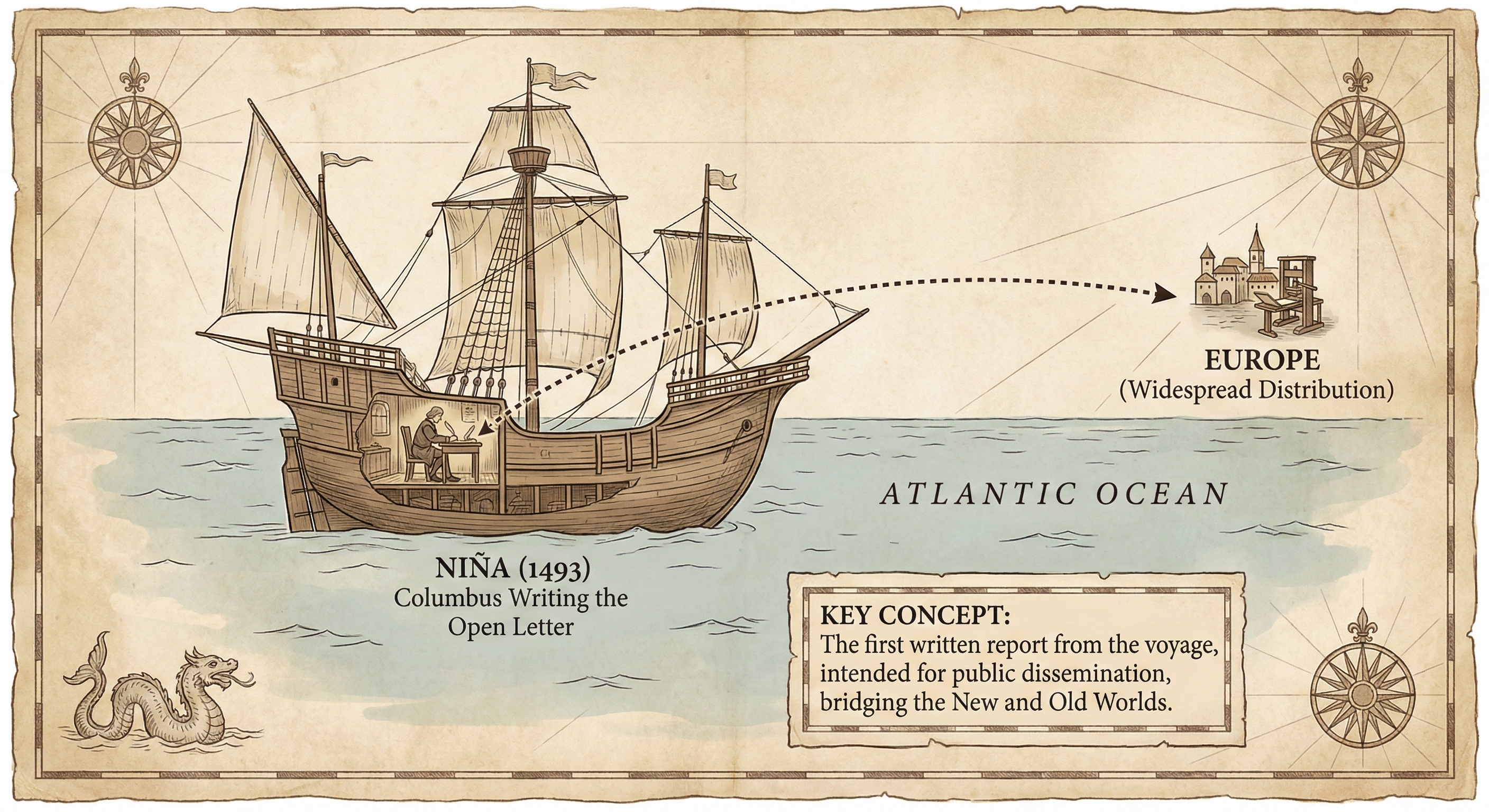

On This Day: 1493 - While on board the Niña, Christopher Columbus writes an open letter (widely distributed upon hi

On February 15, 1493, while navigating the volatile waters of the Atlantic Ocean near the Azores, Christopher Columbus took up a quill to draft one of the most consequential documents in human history. Aboard the caravel Niña, the admiral composed a public report addressed to Luis de Santángel-the finance minister for the Spanish Crown-detailing his arrival in what he believed to be the outlying islands of Asia. This letter served as the official announcement of the existence of the New World to the European public. It transformed a speculative maritime venture into a catalyst for global empire, sparking an information revolution that would reach the printing presses of Rome, Paris, and Basel within months.

Fast Background

By early 1493, the expedition led by Christopher Columbus had reached a point of extreme peril. After departing Spain in August 1492, the fleet of three ships-the Santa María, the Pinta, and the Niña-had spent months navigating the Caribbean. The mission, funded by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, was designed to find a westward maritime route to the lucrative markets of the East Indies. Instead, the crew encountered the islands of the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola.

The situation turned dire on Christmas Day, 1492, when the flagship Santa María ran aground and was lost. This forced Columbus to move his command to the smaller, swifter Niña. As the return journey began in January 1493, Columbus carried the immense burden of proof. He needed to justify the crown’s investment and secure his own future titles and wealth. However, the mid-Atlantic winter was unforgiving. In February 1493, a massive storm separated the Niña from the Pinta and nearly sent the ship to the bottom of the sea.

Fearing that his discoveries would die with him in the Atlantic, Columbus reportedly wrote multiple accounts of his voyage, sealed them in wax, and cast them into the ocean in barrels, hoping they might wash ashore. The letter dated February 15, 1493, was his primary formal report. It was carefully crafted not just as a log of coordinates, but as a persuasive marketing document designed to satisfy his patrons and entice future investors. He described lands of “innumerable” islands, fertile soil, and mountains that “seem to reach the sky,” all while emphasizing the potential for vast quantities of gold and the ease with which the indigenous populations could be converted to Christianity.

Timeline of Key Moments

- August 3, 1492: The expedition departs from Palos de la Frontera, Spain, consisting of approximately 90 men and three vessels.

- October 12, 1492: Landfall is made in the Bahamas. Columbus names the island San Salvador, though the indigenous Lucayan people call it Guanahani.

- October 28, 1492: The fleet reaches Cuba, which Columbus initially believes might be the mainland of Asia or Japan (Cipango).

- December 25, 1492: The Santa María is wrecked on a reef off the northern coast of Hispaniola. Columbus uses the ship’s timbers to build a small fort, La Navidad, leaving 39 men behind.

- January 4, 1493: Columbus departs for Spain aboard the Niña, accompanied by the Pinta, commanded by Martín Alonso Pinzón.

- February 12, 1493: A severe storm strikes the returning ships in the North Atlantic. The vessels are separated, and the crew of the Niña vows to make a pilgrimage to the nearest shrine of the Virgin Mary if they survive.

- February 15, 1493: As the storm begins to subside near the Azores, Columbus writes the “Letter to Santángel,” dating it on board the Niña.

- March 4, 1493: After being forced by weather to seek shelter in Portugal, Columbus anchors in the Tagus River near Lisbon, where he meets with King John II.

- March 15, 1493: Columbus arrives back at the port of Palos in Spain, completing his first voyage.

- April 1493: The letter is published in Spanish in Barcelona. A Latin translation by Leandro de Cosco is subsequently published in Rome, allowing the news to spread rapidly across the European continent.

Inflection Point

The drafting of the letter on February 15, 1493, represents the moment when the “discovery” transitioned from a physical event to a literary and political phenomenon. Until this letter was written and eventually published, the voyage was a state secret and a localized event. The document functioned as the first “press release” of the age of exploration. Columbus made several strategic choices in his writing that would dictate European policy for the next three hundred years.

First, he framed the islands as a land of “marvels,” emphasizing the flora, fauna, and the lack of “monstrous” humans that medieval lore had predicted. This made the New World seem hospitable and ripe for settlement. Second, he purposefully exaggerated the availability of gold. By claiming that he had found mines and that the rivers ran with precious metals, he ensured that the Spanish Crown would fund a second, much larger expedition. Third, he characterized the indigenous populations as “fearful,” “timid,” and “unarmed,” a description that would later be used to justify the ease of conquest and colonization. The letter was not merely a report; it was a manifesto for empire that effectively “sold” the Americas to the European imagination.

What Followed

The publication of Columbus’s letter in the spring of 1493 set off a geopolitical scramble. In May 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued the bull Inter Caetera, which granted Spain the right to all lands discovered west of a specific meridian. This papal decree was eventually codified and adjusted in the Treaty of Tordesillas on June 7, 1494, which divided the non-European world between the Spanish and the Portuguese.

The information contained in the letter also catalyzed a period of intense migration and exploitation. Within six months of the letter’s arrival in Spain, Columbus was sent back across the Atlantic in September 1493 with a fleet of 17 ships and 1,200 men-no longer as an explorer, but as a colonizer. This second voyage marked the beginning of permanent European settlement in the Caribbean and the tragic decline of the indigenous populations due to disease, forced labor, and conflict.

Furthermore, the document spurred what historians now call the Columbian Exchange. The letter’s mention of various plants and the potential for agriculture led to the introduction of European livestock, wheat, and sugarcane to the Americas, while crops like corn, potatoes, and tomatoes were eventually brought back to Europe. The economic and biological landscape of the planet was permanently altered by the chain of events the letter set in motion. Though Columbus died in May 1506 still believing he had reached the fringes of Asia, the wide distribution of his February 1493 letter ensured that his “discovery” would remain the defining event of the dawn of the modern era.

Sources

- Christopher Columbus: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Columbus

- Columbus’s letter on the first voyage: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbus%27s_letter_on_the_first_voyage

- Niña (ship): https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Ni%C3%B1a_(ship)

- Portugal: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Portugal

- New World: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/New_World

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942. (Reference lookup recommended)

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, “Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493.” (Reference lookup recommended)