On This Day: 1849 - The delegation headed by Metropolitan bishop Andrei Șaguna hands out to the Emperor Franz Josep

Title: On This Day: 1848 - The delegation headed by Metropolitan bishop Andrei Șaguna hands out to the Emperor Franz Joseph Generation date: February 13, 2026 Event date: February 13, 1849

What People Commonly Get Wrong

A pervasive myth surrounding the 1848-1849 revolutions suggests that the Romanian national movement within the Austrian Empire was a chaotic, spontaneous peasant uprising fueled solely by agrarian grievances and ethnic hatred. Popular narratives often depict the Romanian leaders of this era as either simple revolutionaries hiding in the Apuseni Mountains or as passive subjects merely reacting to the dictates of the Hungarian Diet in Cluj or the imperial court in Vienna. There is a common misconception that the Romanians of Transylvania, Banat, and Bukovina were politically fragmented, lacking a cohesive vision for their future until much later in the nineteenth century.

However, the historical record reveals a far more sophisticated and unified diplomatic effort. The Romanian struggle was not merely fought with scythes and muskets in the mountain passes; it was waged with ink, legal precedent, and high-level diplomacy in the imperial corridors of power. On February 13, 1849, this diplomatic effort reached its zenith. Far from being a localized riot, the movement produced a coordinated political manifesto that sought to redefine the administrative architecture of the Habsburg Monarchy. The “General Petition” presented on that day was not an amateurish list of complaints but a foundational constitutional document that demanded the recognition of the Romanians as a distinct political nation. It proved that the Romanian intelligentsia and clergy had moved beyond provincialism to envision a unified “national” existence within a federalized empire.

What the Evidence Shows

The events of February 13, 1849, took place against the backdrop of a monarchy in crisis. Emperor Franz Joseph I, who had only ascended the throne on December 2, 1848, was faced with a fragmented empire and an ongoing war with Hungarian revolutionary forces. In this vacuum of power, Romanian leaders from across various crown lands-Transylvania, Banat, and Bukovina-forged an unprecedented alliance.

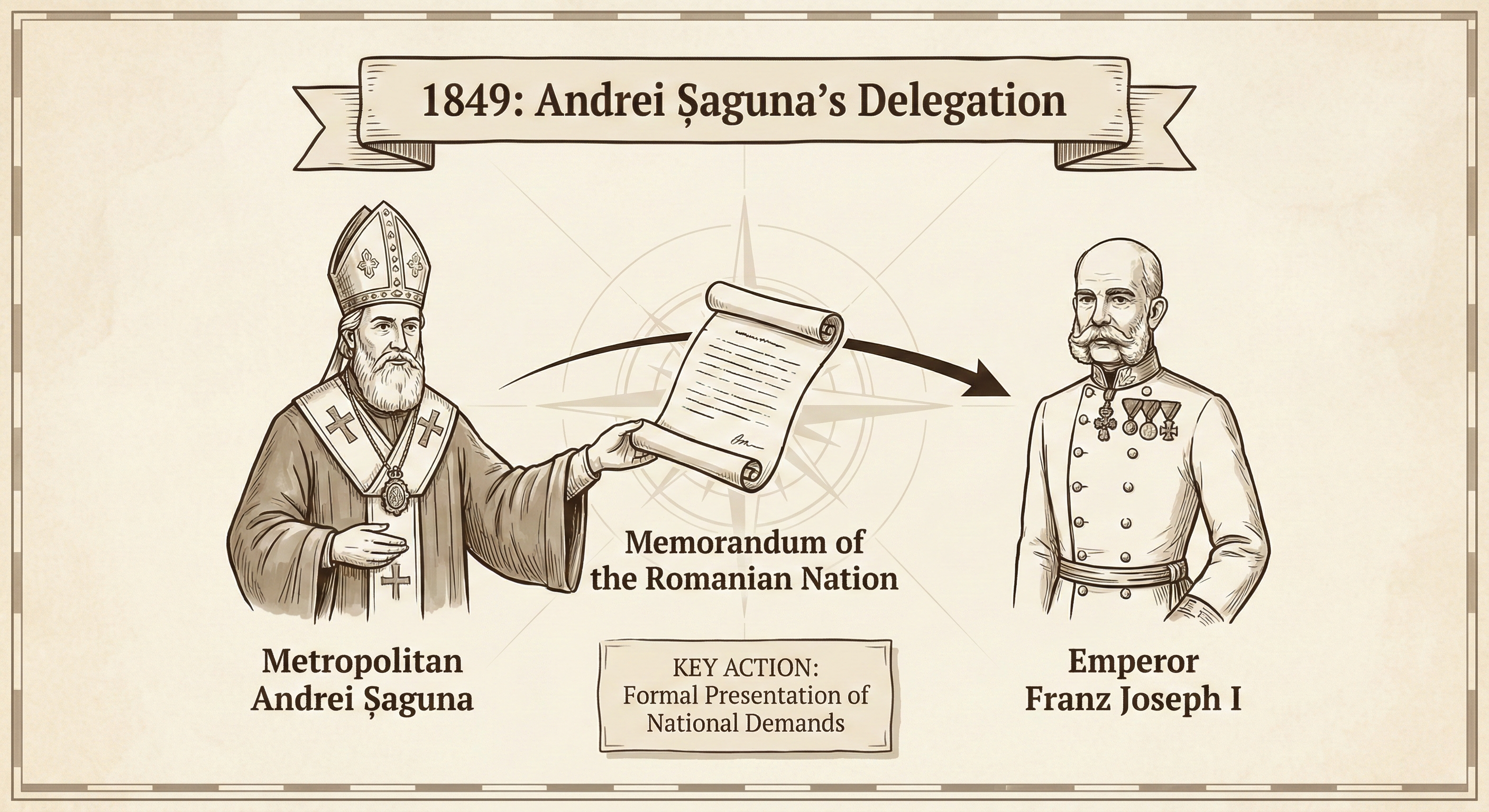

The delegation that arrived at the imperial court in Olmütz (Olomouc) was led by Andrei Șaguna, the Orthodox Bishop of Transylvania. Șaguna was accompanied by prominent figures like Vasile Popp and various representatives from the Romanian communities of the Banat and Bukovina regions. This was a critical distinction: for the first time, Romanians from different administrative jurisdictions of the Austrian Empire acted as a single political body.

The document they presented, the “General Petition of the Romanian Leaders,” was an eight-point program. The evidence from the text shows that the petitioners were not asking for independence, which would have been seen as treasonous, but for “equality of rights” (Gleichberechtigung). They demanded that the Romanian nation be recognized as a constitutional entity, equal to the Germans, Hungarians, and Slavs. They called for the creation of a unified Romanian territory within the empire, governed by Romanian laws and officials, with an annual national assembly and a national guard. The petition also specifically requested that the Romanian language be used in administration and education. This was a calculated move to use the Emperor’s own “March Constitution” rhetoric to secure a legal status that had been denied to Romanians for centuries under the medieval system of “Unio Trium Nationum,” which recognized only the Hungarian nobility, the Saxons, and the Szeklers as political entities.

Main Turning Points

The path to February 13, 1849, was paved by several critical escalations. The first major turning point occurred in May 1848, at the Great Assembly of Blaj. There, approximately 40,000 Romanians gathered to demand national liberty and the abolition of serfdom. This assembly established the ideological framework that Andrei Șaguna would later refine into diplomatic language. It signaled to Vienna that the Romanians were a force that could either stabilize or further disrupt the empire.

The second turning point was the outbreak of civil war in Transylvania in the autumn of 1848. When the Hungarian revolutionary government insisted on the total union of Transylvania with Hungary-effectively erasing Romanian political identity-the Romanians turned toward the Habsburgs. This “loyalist” stance was a strategic choice. By supporting the young Emperor against the Hungarian insurgents, the Romanian leaders believed they would be rewarded with the national autonomy they craved.

The final turning point was the audience itself on February 13, 1849. Andrei Șaguna, a man of immense presence and intellectual weight, presented the petition directly to the nineteen-year-old Franz Joseph I. This meeting forced the imperial court to formally acknowledge the existence of a “Romanian question.” It moved the Romanian cause from the status of a peripheral ethnic disturbance to a central item on the imperial agenda. The delegation’s presence in Olmütz proved that the Romanians possessed a unified leadership capable of navigating the complex bureaucracies of the Austrian state.

What Changed Afterward

The immediate aftermath of the February 13, 1849, petition was a mixture of symbolic victory and administrative frustration. On March 4, 1849, the Emperor issued the “Stadion Constitution,” which did acknowledge the principle of national equality. This was a direct result of the pressure applied by groups like Șaguna’s delegation. For a brief period, the Romanians felt they were on the cusp of a new era. In the years following 1849, the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania was elevated to the status of a Metropolia, and Andrei Șaguna became a Metropolitan bishop, granting the Romanian community a degree of institutional autonomy that served as a surrogate for political statehood.

However, the long-term political goals of the General Petition were never fully realized. As the Austrian Empire moved toward neo-absolutism in the 1850s, the promises of national autonomy were sidelined in favor of centralized control from Vienna. The most significant blow came on February 17, 1867, with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise (the Ausgleich). This agreement created the Dual Monarchy and handed control of Transylvania back to the Hungarian administration, effectively nullifying many of the gains sought by the 1849 delegation.

Despite this eventual setback, February 13, 1849, remains a foundational moment in the history of the Romanian national movement. It established the precedent of “constitutionalism” as a weapon. The legal arguments framed by Șaguna and his colleagues persisted through the late nineteenth century, providing the intellectual and legal basis for the Memorandum Movement of 1892. The petition of 1849 taught the Romanian leadership how to organize across borders-from the Banat to Bukovina-creating a collective consciousness that would eventually lead to the events of December 1, 1918. The diplomatic mission of 1849 proved that the Romanian nation was not merely a demographic fact, but a political reality that could no longer be ignored by the great powers of Europe.

Sources

- Andrei Șaguna: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrei_%C8%98aguna

- Franz Joseph I of Austria: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Joseph_I_of_Austria

- Transylvania: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Transylvania

- Banat: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Banat

- Bukovina: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Bukovina

- Romanians: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanians

- Hitchins, Keith. The Romanians, 1774-1866. Oxford University Press, 1996. (Reference lookup recommended)

- The National Archives of Romania, Sibiu Branch: Documents on the 1848 Revolution. (Reference lookup recommended)