On This Day: 1942 - Second day of the Battle of Bukit Timah is fought in Singapore

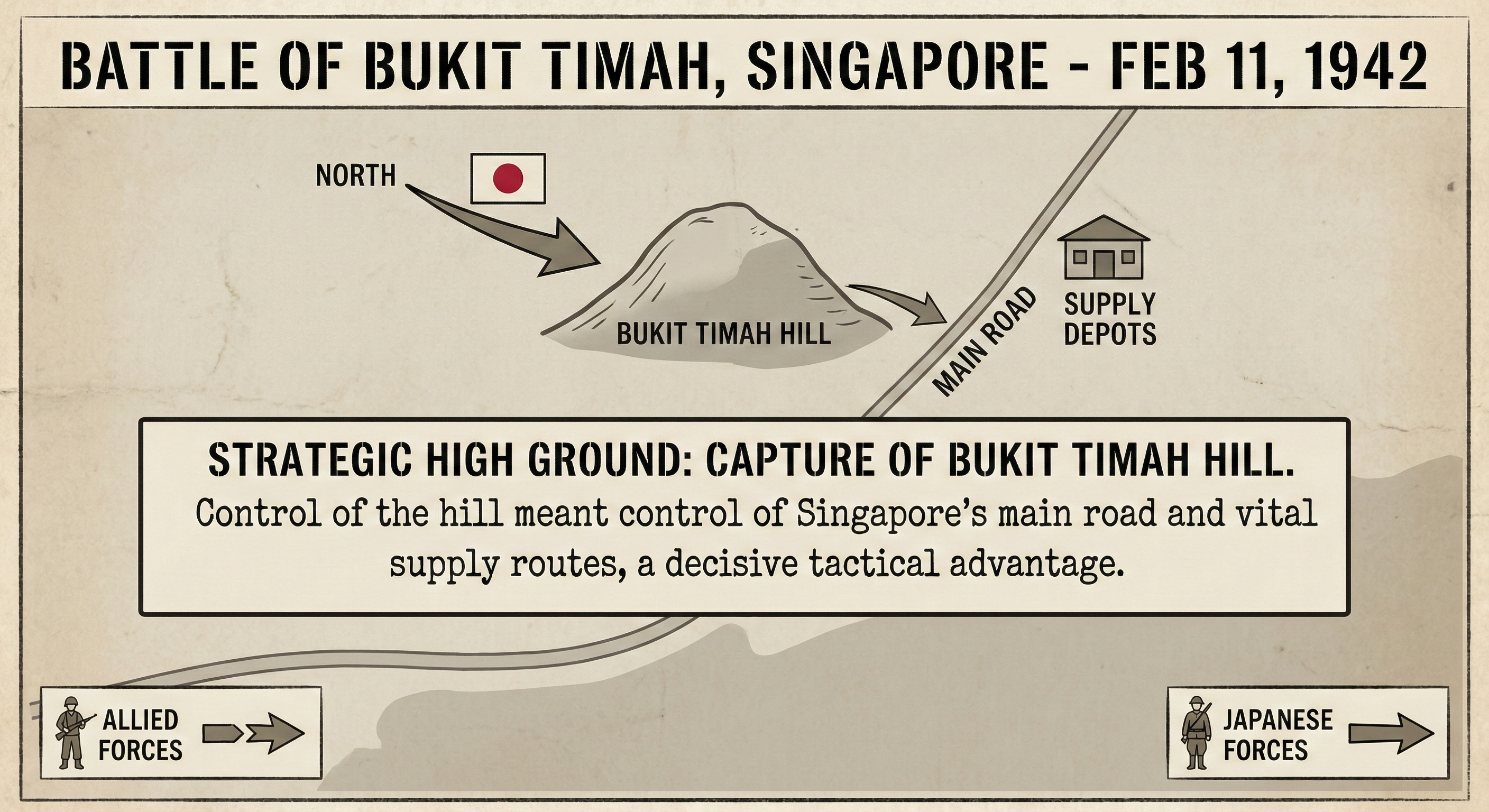

The rapid disintegration of the Allied defensive line along the northwest coast of Singapore Island between February 8 and February 10, 1942, precipitated a desperate retreat toward the island’s central heights. This tactical withdrawal culminated on February 11, 1942, during the second day of the Battle of Bukit Timah, where the Imperial Japanese Army seized the highest point in Singapore along with its critical military supply depots. The capture of this strategic high ground directly stripped the British Malaya Command of its operational depth and essential resources, making the total surrender of the island-once deemed an impregnable fortress-inevitable just four days later.

Immediate Causes

The crisis at Bukit Timah was the direct result of the Imperial Japanese Army’s successful amphibious assault across the Johor Strait, which began on the night of February 8, 1942. General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s 25th Army had achieved a decisive breakthrough against the Australian 22nd Brigade, allowing Japanese forces to establish a firm bridgehead on the island. By February 10, 1942, the Japanese 5th and 18th Divisions had pushed through the “Jurong Line,” a series of unfinished defensive positions intended to shield the heart of the island.

The failure of the Jurong Line was not merely a matter of Japanese military prowess but also of catastrophic miscommunication within the British Malaya Command. General Arthur Percival’s subordinates, fearing encirclement, ordered a withdrawal from the line prematurely. This retreat left the road to Bukit Timah-the central nexus of the island’s infrastructure-virtually open. Bukit Timah held the highest elevation in Singapore, providing a commanding view of the city to the south and the naval base to the north. Furthermore, the area was the location of the British Army’s primary food, fuel, and ammunition reserves.

By the evening of February 10, 1942, Japanese tank units and infantry had reached the outskirts of Bukit Timah village. The British, realizing that the loss of this sector would mean the loss of the entire campaign, hastily organized a counter-attack force known as “Tomforce.” However, the Allied troops were exhausted, fragmented, and suffering from a severe lack of air support, as the Royal Air Force had already been forced to withdraw its remaining planes to Sumatra.

The Event Itself

February 11, 1942, began with intense, close-quarters combat as the Japanese 5th Division launched a concerted effort to clear the village and the hill of Bukit Timah. For the Japanese, the date held immense symbolic significance; it was Kigetsu-setsu, the anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire. General Yamashita was determined to present the capture of the island’s highest point as a gift to Emperor Hirohito.

The fighting on this second day of the battle was characterized by a brutal mixture of tank-led assaults and infantry skirmishes through dense tropical vegetation and rubber plantations. The Japanese 5th Division utilized Type 95 Ha-Go light tanks to bypass Allied roadblocks, moving with a speed that the British commanders had previously deemed impossible in the Malayan terrain. Opposing them were the remnants of the 11th Indian Division and the 22nd Australian Brigade, bolstered by the “Tomforce” reserves.

Despite the bravery of individual units, the Allied defense was disjointed. On the slopes of Bukit Timah Hill, the Japanese 18th Division pushed upward against stubborn resistance. The British had hoped that the natural height of the hill would act as a force multiplier, but the Japanese utilized superior night-fighting tactics and mortar fire to dislodge the defenders. By midday on February 11, 1942, the Japanese flag flew from the summit of the hill, 163 meters above sea level.

As the village fell, the British attempted several desperate maneuvers to retake the supply depots. These depots contained nearly all the petrol and food necessary for a prolonged siege. The fighting surged around the intersections of Bukit Timah Road and Reformatory Road. Casualties mounted on both sides, but the Japanese momentum was fueled by the capture of these very supplies. For the Japanese soldiers, many of whom were nearing the end of their own logistical tether, the discovery of British food stores provided the sustenance needed to continue the final push toward Singapore City.

By the late afternoon of February 11, 1942, the Japanese had secured not only the hill but also the vital Peirce and MacRitchie Reservoirs nearby. This meant the Imperial Japanese Army now controlled the majority of the island’s water supply. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, Yamashita dropped a formal demand for surrender via an airplane over the British lines, addressed to General Percival. Percival, however, chose to ignore the message for the time being, even as his front lines were pushed back to within a few miles of the city center.

Direct Consequences

The immediate consequence of the loss of Bukit Timah on February 11, 1942, was the total collapse of the British defensive strategy. Without the high ground, the Allied forces were pinned into a tightening perimeter around the urban center of Singapore. The loss of the supply depots was perhaps the most crippling blow; within 24 hours of the battle’s end, the British Malaya Command realized they had only a few days of ammunition and food remaining for the one million civilians and nearly 100,000 soldiers trapped in the city.

The capture of the reservoirs also triggered a public health crisis. Japanese forces were able to cut off or restrict the flow of water into the city, where the population had doubled due to refugees. Broken water mains from constant Japanese shelling could not be repaired, and the threat of cholera and thirst became as dangerous as the enemy’s bayonets.

On a tactical level, the fall of Bukit Timah allowed Japanese artillery to be positioned on the heights. From these vantage points, they could accurately shell any part of the city, including the Governor’s House and the harbor. The psychological impact on the defenders was profound. The realization that the “impenetrable” jungle and the “fortress” heights had been taken in a matter of days shattered the morale of the multi-ethnic Allied force. This set the stage for the final, brief stand at Pasir Panjang and the eventual surrender at the Ford Motor Factory-located at the foot of Bukit Timah Hill-on February 15, 1942.

Long-Term Impact

The Battle of Bukit Timah and the subsequent fall of Singapore on February 15, 1942, represented the largest surrender of British-led forces in history. This event fundamentally altered the course of World War II in the Pacific. By removing the primary British naval base in the East, the Japanese were able to secure their southern flank, allowing them to redirect resources toward the invasion of the Dutch East Indies and the threat to Australia.

In the broader context of decolonization, the defeat at Bukit Timah shattered the myth of European military superiority in Asia. The sight of British, Australian, and Indian soldiers being led into captivity by an Asian power resonated across the continent. This shift in perception was irreversible; even after the British returned to Singapore in September 1945 following the Japanese surrender, the colonial prestige that had underpinned their rule was gone. The events of February 11, 1942, served as a catalyst for the nationalist movements that would eventually lead to the independence of Malaysia and Singapore in the mid-20th century.

Furthermore, the battle left a lasting scar on the local landscape and memory. The Japanese occupation of Singapore, renamed Syonan-to (“Light of the South”), began in the shadow of Bukit Timah. The site of the battle became a place of commemoration and, during the occupation, the location of a large Japanese war memorial (the Syonan Chureito). Today, the hill stands as a quiet nature reserve, but the historical events of February 1942 remain the defining moment when the strategic heart of the British Empire in Asia ceased to beat.

Sources

- World War II: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II

- Battle of Bukit Timah: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Bukit_Timah

- Singapore: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Singapore

- The Fall of Singapore by Justin Corfield and Robin Smith (Reference lookup recommended)

- The Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II by Colin Smith (Reference lookup recommended)

- National Archives of Singapore: Oral History Accounts of February 1942 (Reference lookup recommended)