On This Day: 1941 - Operation Grog Bombards Genoa

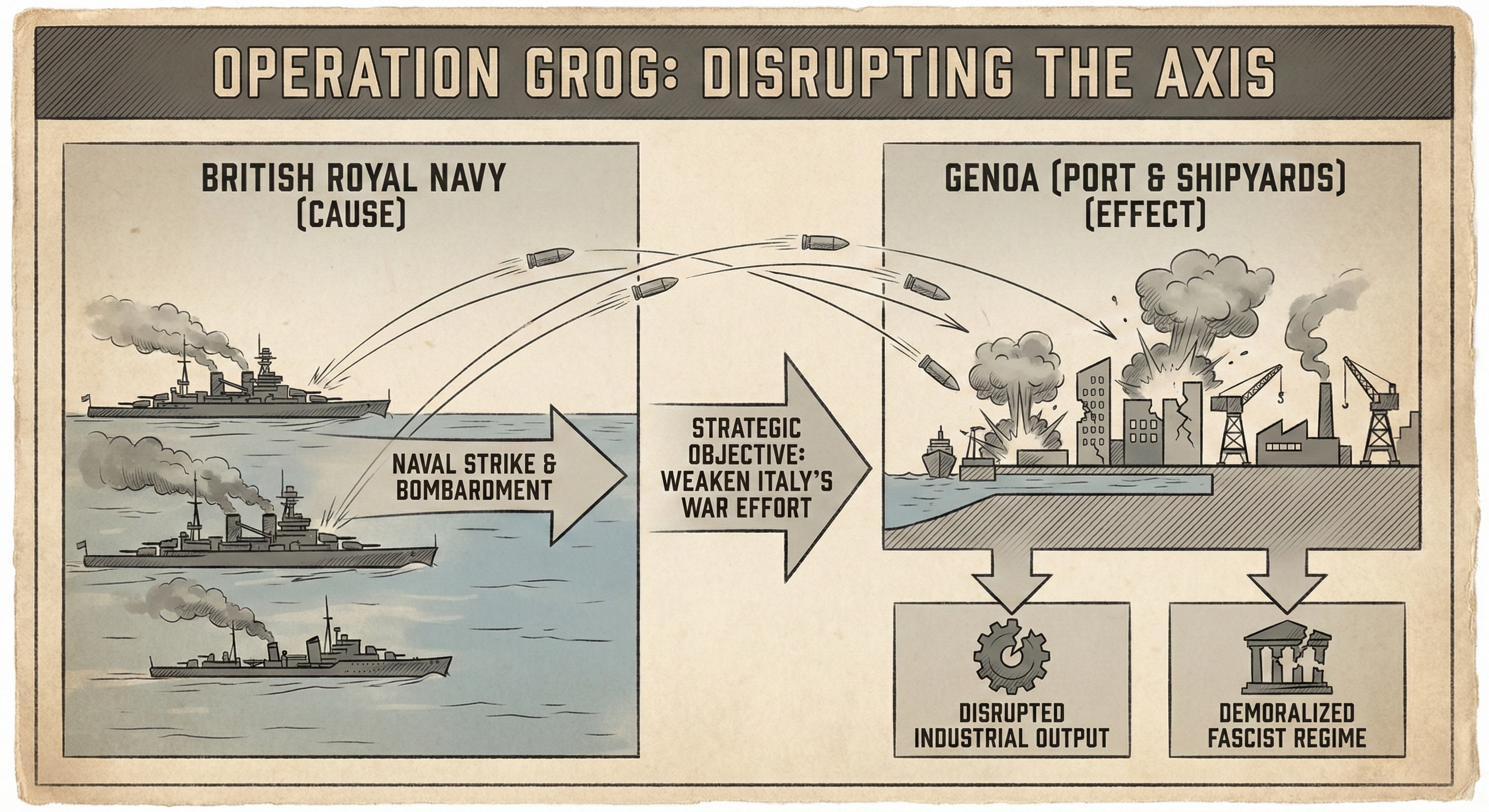

The strategic necessity of demoralizing the Italian Fascist regime and disrupting its industrial output led directly to the British Royal Navy’s daring naval strike known as Operation Grog. On February 9, 1941, this operation culminated in the heavy bombardment of the port city of Genoa, a mission that saw hundreds of high-caliber shells rain down upon the city’s shipyards and historical center. Among these was a 15-inch armor-piercing shell that struck the Cathedral of San Lorenzo, an event that, through the shell’s failure to detonate, spared one of Italy’s most significant architectural treasures and created an enduring symbol of survival amidst the chaos of global conflict.

Immediate Causes

By the dawn of 1941, the geopolitical landscape of the Mediterranean was shifting rapidly against the interests of Benito Mussolini. Italy’s entry into World War II in June 1940 had been predicated on the expectation of a swift British collapse following the fall of France. Instead, the Italian Royal Army found itself bogged down in a disastrous campaign in Greece and suffered a humiliating series of defeats in North Africa during the British offensive known as Operation Compass. These military failures eroded Mussolini’s domestic standing and raised serious doubts within the German High Command regarding the competence of their primary Mediterranean ally.

Winston Churchill and the British Admiralty recognized a critical opportunity to exploit this perceived weakness. To further destabilize the Fascist government and force the Italian fleet - the Regia Marina - into a defensive posture, the British decided to strike at the heart of Italian industrial and maritime power. Genoa was selected as the primary target due to its status as a premier shipbuilding hub and its logistical importance to the Axis supply lines heading toward Libya.

The task fell to Force H, a powerful naval task force based in Gibraltar under the command of Admiral Sir James Somerville. The primary objective was not merely tactical destruction but psychological warfare. The British aimed to demonstrate that despite the presence of the Italian fleet and coastal batteries, the Royal Navy could strike the Italian mainland with impunity. This strategic intent was sharpened by the knowledge that a successful raid would force the Italians to divert resources from the front lines to coastal defense, further straining their overextended military infrastructure.

The Event Itself

The execution of Operation Grog began under a veil of deception. Admiral Somerville led a formidable flotilla out of Gibraltar, including the battlecruiser HMS Renown, the battleship HMS Malaya, the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, and the light cruiser HMS Sheffield, escorted by ten destroyers. To mislead Italian intelligence, the fleet initially mimicked the movements of a convoy protection detail before pivoting north toward the Ligurian Sea.

On the morning of February 9, 1941, a thick mist hung over the Gulf of Genoa, providing the British ships with additional concealment as they moved into firing positions approximately 20 kilometers offshore. At 08:15, the silence of the morning was shattered by the thunder of 15-inch guns. Over the next thirty minutes, Force H unleashed a relentless barrage of 273 heavy-caliber shells, supplemented by nearly 800 rounds from the cruisers and secondary armaments.

The city was caught almost entirely off guard. Coastal batteries struggled to return fire through the fog, and the Regia Marina, stationed at La Spezia, was unable to intercept the British fleet before the damage was done. In the heart of the city, the medieval and Renaissance architecture of the centro storico vibrated under the concussive force of the explosions.

During the height of the bombardment, a 15-inch armor-piercing shell fired from HMS Malaya tore through the roof of the Cathedral of San Lorenzo. The cathedral, a majestic structure dating back to the 12th century, stood as a centerpiece of Genoese religious life. The shell smashed through the nave’s ceiling, crashed into the floor near the altar, and… remained silent. To the astonishment of the clergy and the citizens seeking shelter within the vicinity, the massive projectile failed to explode. Had it detonated, the internal pressure within the stone walls would likely have reduced the historic cathedral to a pile of rubble, causing immense loss of life and destroying centuries of Italian cultural heritage.

Direct Consequences

The immediate aftermath of the raid was a scene of devastation mixed with a localized sense of divine intervention. While the Cathedral of San Lorenzo stood largely intact, the rest of Genoa suffered significantly. The bombardment resulted in the deaths of 144 civilians and wounded 272 others. Industrial damage was extensive; several merchant ships in the harbor were damaged or sunk, and the city’s power plants and railway infrastructure were temporarily crippled.

Politically, the raid achieved the British objective of humiliating the Mussolini regime. The fact that a British fleet could sit off the coast of a major Italian city and fire hundreds of shells without suffering a single hit in return was a propaganda disaster for the Fascists. It highlighted the technical and operational deficiencies of the Italian coastal defense systems and the hesitant nature of the Regia Marina.

In Genoa itself, the “miracle” of the unexploded shell at San Lorenzo became a powerful narrative. The local population, already weary of the war’s hardships, viewed the survival of the cathedral as a sign of protection. The Italian authorities, meanwhile, attempted to downplay the scale of the raid, but the physical evidence of the shell - later defused and emptied of its explosive charge - remained a testament to the vulnerability of the Italian mainland. The dud shell was eventually placed on a pedestal within the cathedral, where it was transformed from a weapon of war into a historical monument.

Long-Term Impact

The bombing of Genoa on February 9, 1941, served as a grim precursor to the intensified aerial campaigns that would ravage Italian cities later in the war. It marked the end of any remaining illusions that the Italian peninsula would be a safe sanctuary from the reach of Allied power. As the conflict progressed, the vulnerability demonstrated by Operation Grog contributed to the shifting internal politics of Italy, fueling the eventual disillusionment that led to the Grand Council of Fascism’s vote against Mussolini in July 1943.

From a military perspective, the raid forced the Axis to reconsider their naval strategy in the Mediterranean. The Regia Marina became increasingly “fleet-in-being,” staying largely in port to avoid catastrophic losses, which in turn conceded greater control of the sea lanes to the British Royal Navy. This control was vital for the eventual success of the Allied invasions of Sicily and mainland Italy.

The Cathedral of San Lorenzo remains a focal point for this history. As of February 9, 2026, the shell is still displayed within the cathedral, its presence serving as a permanent reminder of the fine line between preservation and total destruction during the Second World War. The event is often cited by historians and cultural heritage experts as a primary example of the “near misses” that defined the survival of European art and architecture during the 1940s. The shell is more than just a piece of rusted metal; it is a physical link to the morning of February 9, 1941, a day when the trajectory of a single projectile could have erased a city’s soul, but instead became a footnote in the story of its resilience.

Sources

- World War II: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II

- Bombing of Genoa in World War II: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombing_of_Genoa_in_World_War_II

- Cathedral of San Lorenzo: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathedral_of_San_Lorenzo

- Genoa: https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Genoa

- The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940-1943 by Jack Greene and Alessandro Massignani (reference lookup recommended).

- Churchill’s Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation, 1939-1945 by James Davies (reference lookup recommended).